By Scott Campbell

Shortly after arriving in Palestine in 2012, a comrade invited me to a demonstration in front of al-Muqata’a in Ramallah, the seat of the Palestinian Authority in the occupied West Bank. It was a significant symbolic event, being the first protest against the PA directly in front of its headquarters with about 100 people holding signs on the sidewalk condemning PA President Mahmoud Abbas’ decision to hold negotiations with Israel. Nothing much happened, but that nothing much clearly irritated the PA.

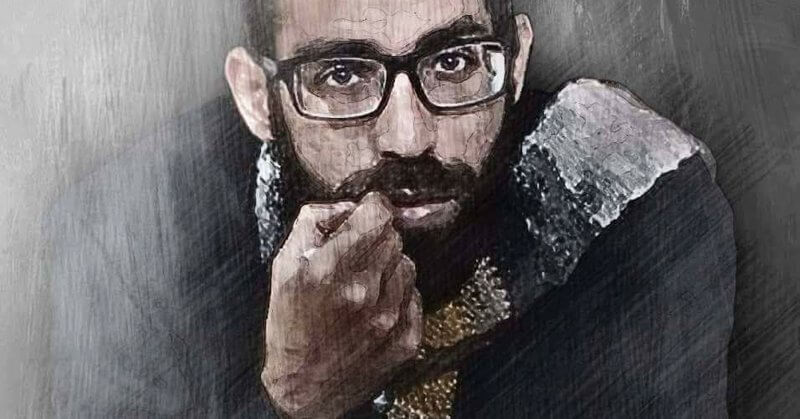

Following the protest, several people met at a nearby café. That was the first time I met Basil al-Araj. Similarly, nothing much happened, but the more time I spent in Palestine, the more and more frequently I found myself in Basil’s company. He spoke passable English, and aside from translations by others, that was how we communicated given that I embarrassingly managed to live there for more than a year and not learn Arabic.

From the first, Basil struck me as intelligent, passionate and stubborn. He was always carrying around political and theoretical texts and offering up for reflection or discussion what he had been reading. He had an iconoclastic streak that he would unleash with rhetorical flourish. A specialty of his was knowing precisely what to say and when to say it in order to best get under your skin, in the friendliest of ways. Our discussions around anarchism were guaranteed to end with comradely frustration on both sides. I write this not to besmirch him, but with a smile on my face, remembering the complex and dynamic individual that he was. I miss all of it.

One morning while my parents were visiting, several of us gathered for breakfast at a friend’s apartment. Basil was there and midway through the meal began peppering my father with questions about his thoughts on George Habash, Leila Khaled and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. It was intended purely to make my father uncomfortable, which Basil succeeded in doing, and I could tell by the smile and gleam in his eye that Basil was thoroughly enjoying himself. I wanted to throttle him at the time. Now all I can do is laugh.

Months after first being impressed with Basil as smart, dedicated and humble, I learned what a good friend he could be. After an extended period in Palestine, I was having difficulty getting treatment for an ongoing medical condition. When this was shared with Basil, he immediately offered to help. Using his training as a pharmacist, he made several hours-long trips up from al-Walaja to Ramallah to bring me the treatment I needed. Not once did he allow me to pay for the medication or his travel expenses. His efforts sustained my well-being and I will never forget that. In doing so, he taught me the meaning of solidarity and mutual aid.

Upon leaving Palestine, I had little contact with Basil and none for the past year or more. But when I opened my email on the morning of Monday, March 6, it was there. That notice which feels more like a matter of when, not if: that the Israelis had stolen a friend. The casual email routine was shattered as first disbelief then deep sadness sank in. I could do nothing but weep. Given the impact with which it hit me, I cannot even begin to imagine the blow such news struck to those who spent years in his company. I offer my most sincere, heartfelt condolences to his family, friends and comrades. The assassination of Basil al-Araj is a tremendous loss to a huge number of people, as evidenced by the international outcry, the ongoing demonstrations and the thousands who came to his funeral – once the Israeli occupiers deigned to return his bullet-riddled body to his family.

A recounting of the tribulations Basil faced his final year on this earth can be found elsewhere. Reflecting on what he went through, while the grief remains, I am filled with enormous admiration, pride and rage. Rage that the Palestinian Authority jailed, tortured and painted a target on Basil. Rage that even after he was martyred, the PA held legal proceedings against him while beating Palestinians in the streets, including Basil’s father, who were mourning and condemning the PA’s subservience to the occupier. Rage that for seven months, Basil was forced underground by the Israelis, who endlessly harassed his family and raided their home more than ten times. Rage that after a life lived under Israeli apartheid, in the pre-dawn hours of a Monday morning Basil was alone under a two-hour hail of Israeli bullets before he finally succumbed, murdered for refusing to bow, murdered for being an unapologetic Palestinian in Palestine.

I admire and am proud to have known Basil, even if for a short time. I admire his independent political acuity, his ability to blend anti-authoritarian tendencies, an international perspective and Palestinian liberation. And how that intellectual rigor led not only to resistance but also to being a true friend and comrade. For him, the two were intrinsically linked. I admire how he withstood the injustices inflicted upon him by the PA and gained his release with a hunger strike. I admire how he stayed underground for so long in a militarily occupied territory. And lastly, I admire that when the Israeli occupation forces came for him, his final decision epitomized the trajectory of his life: to resist. He had already written his will. Alongside his gun he had his books, Gramsci included. And as he departed, in his own blood he wrote, “Humiliation is now a thing of the past.”

Thank you, Basil, for all you did for all of us. Journey well, friend. Your memory and path are held by those who remain.