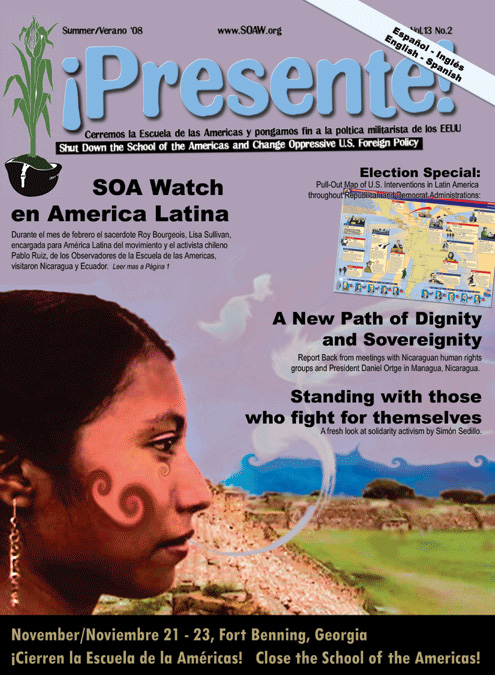

[ The cover image of this issue was created by Simón P. Sedillo.

It portraits Tonantzin, a mother goddess and lunar deity from Aztec mythology, also known as the “Mother of the Corn.” ]

by Simón Sedillo

Originally published in the Summer 2008 issue of ¡Presente! – newspaper of SOA Watch

Neoliberals believe that somehow they have finally discovered a socially responsible, or socially democratic, way of taking people’s land, labor, and resources by force, for profit.

It’s not possible. This is the myth of neoliberalism. This imposed political economy reduces human beings and natural resources into variables in an economic equation. Every day the human variable in this equation is considered more expendable. Indigenous people, farm workers, women, youth, and poor people everywhere are reduced to variables in this equation. When no longer considered economically viable by the powers that be, communities become economically expendable. If a group of people can be treated as disposable for “not fitting in,” imagine how that group is treated when they organize or resist this imposition. Historically they have been treated as a virus which must be eliminated.

This is the same kind of genocide upon which the United States of America was founded. Somehow most U.S. citizens have managed to detach themselves from their nation’s history to the point of ignoring its present. Native children were still being put in “boarding schools” by the U.S. Army just over 70 years ago. The School of the Americas has made a science out of terrorizing communities in resistance throughout Latin America. The most conservative estimate provided by the Iraqi Health Ministry, claims a total of 151,000 violent deaths from March 2003 through June 2006.

What once was easily-identifiable militarism in Central America has devolved into the para-militarization of indigenous communities throughout southern Mexico. In Oaxaca, many of the atrocities committed against indigenous communities are disguised as agrarian land disputes between neighboring communities. Some are orchestrated well enough to confuse the very paramilitaries of their role in this systematic form of state-sponsored repression. The disputes can be between different tribes, the same tribe, and mestizos. These strategies are not new, just a continuation of dividing then conquering.

The greatest threat to the national security of the United States has always been grassroots, community-based organizing for self-determination, people sharing the idea that they are capable of taking care of themselves. That is the threat Native Americans posed, and the threat that the people of Oaxaca, like many others, continue to pose. In 2005-2006 the Department of Geography at Kansas University in Lawrence, Kansas received a $500,000 grant from the Department of Defense to map communally-held indigenous lands in Oaxaca, Mexico. The Foreign Military Service Office (FMSO) at Fort Leavenworth is providing the grant money. Fort Leavenworth was the epicenter of westward expansion by the U.S. into Native territory. Today the FMSO assesses “asymmetric” and “emerging” threats to the national security of the U.S. Asymmetric threats are defined as guerrilla armies and terrorist organizations, while emerging threats are clearly being defined as social movements.

The greatest threat to the national security of the United States has always been grassroots, community-based organizing for self-determination, people sharing the idea that they are capable of taking care of themselves. That is the threat Native Americans posed, and the threat that the people of Oaxaca, like many others, continue to pose. In 2005-2006 the Department of Geography at Kansas University in Lawrence, Kansas received a $500,000 grant from the Department of Defense to map communally-held indigenous lands in Oaxaca, Mexico. The Foreign Military Service Office (FMSO) at Fort Leavenworth is providing the grant money. Fort Leavenworth was the epicenter of westward expansion by the U.S. into Native territory. Today the FMSO assesses “asymmetric” and “emerging” threats to the national security of the U.S. Asymmetric threats are defined as guerrilla armies and terrorist organizations, while emerging threats are clearly being defined as social movements.

The first step in standing in solidarity with people who fight for themselves is understanding that their fights are considered threats to the powers that be.

Today we face “Imperial activism,” the idea that activists know better than the communities with whom they stand in solidarity. U.S. citizens have, in particular, harnessed this notion of “empowerment” of women, people of color, the indigenous, workers, youth or other groups. This notion of empowerment places power in the hands of the activist and negates the power of the people who are resisting for themselves.

This dynamic validates charity and not solidarity. Real solidarity is more about sharing, collaborating, and contributing to self-empowerment, as opposed to feeling good about handing out some aid. It is important to learn first, before teaching anything. Many indigenous communities have centuries of resistance to share and teach. The best way to walk or move forward in solidarity is by asking first about what may be needed or what may be a problem. Walking by asking, then teaching by learning.

To this end, I can only testify to my experience as a Chicano community-based organizer who chose to stand in solidarity with the people of Oaxaca. In 2005, in collaboration with Austin Indymedia, I finished a Oaxaca solidarity film called “El Enemigo Común.” After production the compas in Oaxaca made it clear that they wanted to learn how to shoot and edit video themselves. I had to learn what I could and should teach, and why I should teach that. In my case I had to learn how to edit video, then how to teach this skill.

I started as a solidarity activist but ended up a teacher and, most importantly, a student. I learned a lot about my privilege to learn and my responsibility to teach. In the United States I could learn video and audio to teach in Oaxaca. There, in turn, I could learn about methods of community-based organizing and teach about them in my community here.

Residents of the U.S. have more to learn than teach. The peace in which many U.S. residents believe is a lie. There can be no peace without dignity, justice, and liberty for everyone, everywhere. The more that people in the U.S. believe in this false peace, the more they validate its means: terror.

In 2002, at a farmworker sit-in at the state capitol in Oaxaca City, a compa leaned over to me and said, “Do Americans not realize that their peace is our terror? And if they did, would they care?” This peace has been and continues to be built on the back, sweat, and blood of others. To truly stand in solidarity with the many others fighting for themselves everywhere, people in the U.S. who care about justice have to challenge their ideas about peace. What are you willing to sacrifice for others to have peace as well? True solidarity comes from sacrifice, the recognition of privilege and the responsibility that comes with that privilege. We must be accountable to the whole of humanity at all times, not just to those we choose when it is convenient to do so.

—

source: http://www.soaw.org/presente

Simón P. Sedillo created the image of Tonantzin that was used as the cover image of the Summer ’08 issue of Presente.

In Aztec mythology, Tonantzin is a mother goddess and lunar deity. Some anthropologists believe that Our Lady of Guadalupe (an indigenous manifestation of Christ’s mother Mary and patroness of Roman Catholic Mexico) is a syncretic and “Christianized” Tonantzin. Mexico City’s 17th-century Basilica of Guadalupe — built in honor of the virgin and perhaps Mexico’s most important religious building–was constructed at the base of the hill of Tepeyac, believed to be a site used for pre-Columbian worship of Tonantzin.

Among the titles and honorifics bestowed upon Tonantzin are “Goddess of Sustenance”, “Honored Grandmother”, “Snake”, “Bringer of Maize” and “Mother of the Corn”. Other indigenous names for her include Chicomexochitl (“Seven Flowers”) and Chalchiuhcihuatl (“Woman of Precious Stone”). Tonantzin is honored during the movable feast of Xochilhuitl.

The goddess Tonantzin shares characteristics with similar Mesoamerican divinities Cihuacoatl and Coatlicue, all of whom may have been drawn from common origins.

http://www.soaw.org/presente/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=156&Itemid=69