By Claudio Albertani

I attended the Second Statewide Conference of the Popular Assembly of the Peoples of Oaxaca (APPO) on February 20, 21, and 22, 2009, at the Teachers’ Union Hotel in the capital city, as an invited guest. The first Conference (November, 2006) had launched an ambitious plan of struggle with regards to social justice, workers’ rights, and the defense of indigenous peoples and the environment. The APPO was the main reference point for the social struggle in Mexico and had strong international recognition.

We now know that the disastrous move towards today’s rightwing control of the country was already underway. In a way, Oaxaca was a refreshing anomaly. The corrupt, despotic government of Ulises Ruiz had generated a massive, creative, and hopeful response here. Without denying their differences, teachers, workers, indigenous communities, artists, migrants, libertarian collectives, militants of political organizations, and people not affiliated with any party had come together in the APPO, an experience that was unprecedented and, at once, immemorial. Unprecedented, because grassroots participation temporarily eclipsed the limited sphere of local leftist political organizations, and immemorial, because it was linked to the self-generative traditions of Mesoamerican indigenous peoples.

Two years and several months later, the circumstances that gave rise to the movement ––an especially sinister government and an extraordinarily creative people–– are not only still in play, but are now heightened. Against all expectations, Ulises is still there and the dirty war, as well, even though it’s been metamorphasized so as not to frighten the tourists. The freedom of most of those arrested in 2006 has been won, but prisoners from Loxicha, Xanica, San Blas Atempa, and a few APPO members are still in jail.

Repression has become more discreet; there are no anti-riot tanks or Federal Preventive Police (PFP) agents patrolling downtown streets, but peace is far from real. Now operations are mainly carried out against teenagers in marginalized barrios and in remote regions like the Triqui area, where people are undergoing an intolerable state of violence. Mega projects are still in process, such as the Paso de la Reina hydroelectric dam and reservoir that the Federal Electricity Commission plans to build over the Río Verde, regardless of local opposition. Gender crimes are also on the rise. According to official statistics, in the first eleven months of 2008, 55 women were assassinated in Oaxaca, eleven of them Triquis.

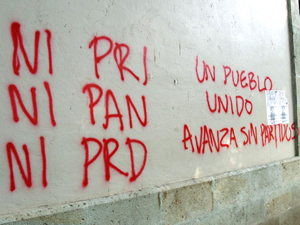

The goals of the Second Statewide APPO Conference included naming a new collective leadership body, assessing the current situation, and dealing with it by recapturing the spirit of 2006. Did they achieve them? The balance is weighted. In the first place, this was a smaller Conference. Some important groups with a social base in communities withdrew, like the Indian Organizations for Human Rights in Oaxaca (OIHDO), Magonista-Zapatista Alliance (AMZ), and the Popular Indigenous Council of Oaxaca “Ricardo Flores Magón” (CIPO-RFM); or opted for not participating, like Dignidad Rebelde, as well as a good number of libertarian collectives because they now see the APPO as nothing more than a cadaver whose remains are disputed by opportunist politicians seeking candidacies in the upcoming elections. With things as they are, several irate kids made their presence felt outside the Hotel, spray painting the walls and carrying on a noisy protest demonstration.

Other groups, like Oaxacan Voices Constructing Autonomy and Freedom (VOCAL), Casota Collective, and several autonomous representatives of communities and neighborhoods opted for doing battle from within, actively participating in the preliminary organization and speaking out in the workshops. These were organized into five areas: 1) the Oaxacan peoples’ movement and its current international, national, and statewide contexts; 2) a critical and self-critical assessment of the APPO movement from 2006 to the present, and its prospects; 3) basic APPO documents; 4) the country’s democratic transformation, with justice and freedom; 5) list of demands, plan of action, and policy on negotiation and alliances.

In practice, the discussion invariably revolved around three obsessive points: 1) whether or not to participate in the elections in the name of the APPO; 2) whether or not to negotiate with the State; and 3) whether to decide by consensus or by majority vote. The forces were unequal since traditional groups like the Stalinist Popular Revolutionary Front (FPR) and the New Left of Oaxaca (NIOAX, now deceptively re-baptized as the “Oaxaca Commune”], plus related groups in Section 22 of the teachers’ union, were over-represented and even brought in on buses in true PRI party style. Upon realizing that they were being used, some community representatives like the delegate from San Pedro Gregorexe withdrew, horrified.

The directives (from FPR and NIOAX) were clear: impose by any means possible a strategy of alliances with the so-called leftist political parties, running joint slates in the upcoming July elections. In a situation like this, the opposition didn’t have an easy time of it, but it would be a mistake to say they were defeated. Their first victory, albeit symbolic, was the removal of the pictures of Stalin, Lenin, Marx, and Engels, put up, as usual, by the FPR.

There were some outstanding presentations. On Friday, February 20, the Zaptotec painter Nicéforo Urbieta, member of the Culture Commission of the first provisional APPO leadership council, shared a meaningful anecdote. In the summer of 2006, when the movement was at its height, the APPO used a logo made up of an ear of corn and two bastones de mando (indigenous staffs of command). According to Urbieta, the corn stands for spiritual strength and the Mesoamerican peoples’ way of being in the world. An expression of indigenous communality, the staffs of command symbolize Quetzalcóatl and Tezcatlipoca, the universal principles of creation and destruction.

The logo graphically represents the distinctive characteristics of a movement reclaiming its indigenous roots. At the first APPO Conference, however, the political organizations imposed a more banal logo “by majority vote”: clenched fists and the abiding red star on the background of a demonstration framed in a map of Oaxaca. This transformation isn’t coincidental. According to Urbieta, it represents the return to a political approach in which the social movements are loot for achieving the (now devalued) “dictatorship of the proletariat” or even a simple seat at the Conference.

On Saturday the speeches by Gustavo Esteva and Benjamín Maldonado stood out. Gustavo laid out a brilliant analysis of the international economic crisis, relating it to the national situation and the social movement in Oaxaca. We’re at the end of a historical cycle, he noted. But which one? Nobody is absolutely sure about that. The (few) honest economists are giving notice that all the predictions have failed. It’s not just a simple phase of prosperity that’s run out of steam; blind faith in the market has failed, that thing called “neoliberalism,” which was neither new nor liberal.

The mechanisms of the 1930’s, he continued, accentuated stability and prudence. Neoliberalism destroyed these aspects, creating legions of discontent the world over. Today, 100 people own more measurable wealth than all the rest of humanity put together (and, I would add, are ready to defend it, no matter what it takes). Some think we’re experiencing the suicide of capitalism due to the arrogance of a few, but it could be an interminable death that ends up killing us all.

Deglobalización? What we have here is a deceptive concept because globalization began centuries ago; maybe the novelty is that the United States has lost its imperial status. Formal democracy also died. Should we mourn? No. It was an elitist regimen: a benevolent oligarchy in the best of cases and a foul dictatorship in the worst. And finally, the Enlightenment died, that utopia of capitalism with equality for all.

In the name of “democracy”, we are now experiencing the specter of control over the population and individuals. The imperative is to beat back any and all dissidence. Governments extol the criminal use of power in all its forms in their attempt to stay where they are. What just happened in Gaza may be a general rehearsal of what is likely to happen to all of us. They weren’t trying to do away with Hamas; to the authorities, nothing looks more like terrorism than ordinary people, and maybe they’re right.

In Mexico there are two presidencies and no government. Oaxaca has the best indigenous legislation on the continent. And what is it worth? It’s violated daily by all three branches of government. To get out of the crisis, Esteva insisted, we need other instruments. Fortunately, a growing number of people are realizing that elections are always manipulated and that even those who are chosen in clean elections don’t respect the majorities that elected them.

The insinuation was evident and those of us who were present couldn’t help think about the insipid, third-rate performance in the State Legislature of Representative Zenén Bravo, FPR militant elected in 2007 on the Convergencia slate, the party of counterinsurgency in Chiapas…

The new era, the speaker concluded, will begin when we learn how to formulate new concepts. Soviet type socialism is no longer an option because even though it was first defined by a communal spirit, it turned into bureaucratic statism and collectivism. It met its death through self-destruction.

In 2006, Oaxaca was the forerunner of what’s now going on in the world in two ways: creativity and state repression. In order to regenerate the APPO, what we don’t need to do is turn back to old party politics and elections. The only option is to strengthen horizontal, decentralized structures in the communal tradition of the peoples of Oaxaca. Here, Esteva’s diagnosis was unequivocal: if the APPO is not able to resolve these basic aspects, it will become a sect.

In turn, Benjamín Maldonado framed the APPO’s experience in its Mesoamerican context. Colonialism is not dead, he explained. With Independence, Spanish domination ended, but it’s the national society that now dominates indigenous peoples in a way that Benjamin defined as “volcanic,” in other words, particularly destructive. In the face of the new situation, the peoples continue to resist as they have always done. How? Through their communal life, which has three main aspects: 1) communal lands; 2) institutions such as tequio (mutual support), the assembly of the people, and the fiesta of the people; and 3) a deeply rooted communal mentality.

This is what is defined in Oaxaca as “communality,” the vitality that feeds indigenous resistance. A resistance that we might express in Western terms as “self-generated.” The peoples live in a self-generated way inasmuch as they resist the tutelage of the State and “separate” institutions like political parties. In this sense, the APPO carries on this historical experience, and behind it are the indigenous peoples.

Today, the indigenous peoples face three main dangers: political parties that are infiltrated in their assemblies, emptying them of content; indigenous education that fragments communal values at the same time that it “nationalizes” them; and protestant sects that annihilate their social structures. This is why the indigenous movement aims to “reconstruct” the peoples. The APPO must also rebuild itself by getting away from politicking and returning to its indigenous roots and the experience of urban youth who discovered their own “communality” in the heat of the barricades of 2006.

The notion of “seizing power” is a hollow phrase, first of all because the experience of the betrayed revolutions of the 20th century tells us that power is not an object to be taken, but instead a social relation to be constructed, and furthermore, because such a seizure has no base in local “counter-powers” that have joined together. In this sense, the APPO could be transformed into a federation of assemblies instead of continuing to exist as one peoples’ assembly. The movement, concluded Maldonado, can be rebuilt by starting with the consolidation of regional powers.

It seems to me that the addresses by Urbieta, Esteva, and Maldonado expressed the feelings of many of those present despite the unfavorable conditions in which the Conference took place. Sunday’s agenda was marked by frequent interchanges between the defenders of electoral politics and the young people of VOCAL, who waged a pitched battle, without backing down. It wasn’t in vain. At the end of an exhausting debate that lasted until 11 o’clock Monday morning, February 23, not a single one of the three points disturbing the “politicians” had been resolved in their favor.

The final declaration of the Conference states that “this assembly is not a political trampoline. Any comrade who wants to participate in the electoral process will have to publicly resign from his or her seat in the APPO 5 months before filing.” (Thus the deadline for the July elections has already expired.) Likewise, the document demands the “immediate, unconditional release of all arraigned political prisoners and fugitives,” reiterating that “the APPO does not have a policy of negotiating, given that it does not recognize the local or federal government.”

The machinations, however, don’t stop here. Even though some council members were designated, the delegates from the strategic Valley and Isthmus regions are still pending. And that’s where the “politicians” could regain ground. The debate doesn’t matter to them, and neither do ideas. All they’re interested in is staying put in the movement leadership and in maintaining control over the relationship with the news media. These same media, far from reporting on the true milestones of the Conference, opted once again for branding as “provocateurs” the very people who’ve struggled against all odds to defend the spirit of 2006. (See, for example, the article accusing people associated with David Venegas, “el alebrije” of trying to tear the APPO forum apart: Pedro Matías, “Pretendieron alebrijes reventar foro de la APPO”, Noticias, 21 de febrero).

Oaxaca, March, 2009