Note: This photo essay is dedicated to the memory of community defender and environmental activist Noé Vázquez, who was brutally murdered on Aug. 2, 2013 as he was preparing for his hosting of the opening ceremony for the 10th anniversary celebration of the Mexican Movement of Men and Women Affected by Dams and in the Defense of Rivers (MAPDER). Text and photos by Jonathan Treat

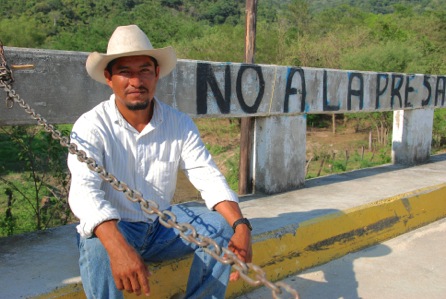

The blockade is simple, but its implications profound. A thick steel chain across the only bridge entering the small town of Paso de la Reina, municipality of Santiago Jamiltepec of roughly 500 residents on Oaxaca’s southwestern coast, is attended daily by men and women who prevent the entry of anyone connected with a proposed hydroelectric dam project on the Rio Verde. And for four years that strategy has been successful.

Local community defenders, together with people from other communities and members of Counsel of Peoples United for the Defense of the Rio Verde (COPUDEVER), came together recently at El Zanate, a lush green riverside site near the entrance to the town, to celebrate the fourth anniversary of their ongoing, nonviolent blockade, and their success in halting the project to date.

“We’re here to celebrate this successful and peaceful blockade. Since we decided to put up the blockade at the entrance to our ejido (communal land holding) in July 2009 to prevent anyone from the CFE (Federal Electric Commission) from entering to do their surveys and studies for the project, none of them has been able to do that work. So this is a very significant day, celebrating with our compañeros our decision to put the first stone in the way of the dam project,” explained Eva Castellanos Mendoza, local community activist and a member of COPUDEVER. “And it’s a triumph. The blockade has worked. If it hadn’t been here, I think the CFE would have completed their work and probably started with construction of the dam.”

Engineers from the Mexican Federal Electric Commission (CFE), surveyors and government officials, at times accompanied by police, have all tried on various occasions to pass the blockade—each time without success. CFE engineers even tried to conduct surveys for the project by skirting the blockade and coming upriver in an inflatable motorboat. Townspeople on watch noted their surreptitious attempt and called together a community commission, who confronted them and escorted them out of town—without their boat and surveying instruments.

“They were almost ready to cry because we’d kept their boat and their equipment,” explained Manuel Sánchez Riaño. “They were pleading with us, saying how expensive it was. We gave it all back to them, but told them not to come back.”

Opponents of the proposed hydroelectric project note that in addition to the negative environmental impacts, the loss of agricultural lands would deprive residents of agricultural and fishing areas, forcing many to migrate – often ripping community’s cultural and social fabric. Hence the ongoing and widespread opposition to the project.

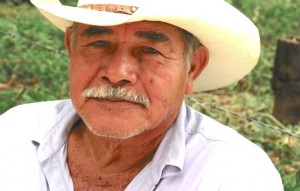

“This is our territory. This is where we live and work. So we’ve been helping to maintain this blockade. We’ve never stopped, never left this struggle. And we haven’t let anyone from the government or the CFE who wants the dam project to pass this bridge,” added Martiniano Martínez Martínez, Assistant Secretary of the Community Commons (Bienes Comunes), of Tataltepec de Váldez. “And we’ll continue to struggle and defend our territory. No one is going to enter and destroy this land.”

Maintaining the blockade these four years has not been easy. The blockade is manned full-time during daylight hours, meaning time away from work. And there are risks – those opposing the project have consistently been harassed and threatened. Throughout Mexico environmental and community activists have been targets of repression, including assassinations.

“At times the struggle has been difficult and worrisome, but we’ll continue until we’ve won our struggle and stopped this dam,” said Flavio Cruz León, Municipal President of Paso de la Reina. “These are our lands, if we don’t defend them, what will our children think? What will we leave them?”

The blockade at the entrance to Paso de la Reina has been a unifying force for people from the 43 communities in the region that are at-risk of negative environmental, cultural and social impacts of the proposed hydroelectric dam project. Since coming together in 2007 to form COPUDEVER, the grassroots organization has galvanized major resistance and worked to develop effective, nonviolent strategies for stopping the Paso de la Reina hydroelectric project.

But the unity present during the anniversary celebration hasn’t always been there, and has taken years of meetings and organizing to bring communities in the region together. When The Mexican Federal Electric Commission (CFE) project engineers first came to speak with some residents in Paso de la Reina about the many benefits the hydroelectric project would bring – jobs, ecotourism, and development – the residents of the town were divided about whether to accept or oppose the project.

But there has been a consistent lack of transparency regarding the full implications and impacts of mega development projects on communities in Mexico (and beyond). Mexico’s environmental ministry, the Secretariat of Environment and Natural Resources (SEMARNAT) and the National Water Commission (CONAGUA) – incredibly – publicly deny any knowledge of the proposed Paso de la Reina Hydroelectric Project

So, not surprisingly, some residents of Paso de la Reina who’d heard about negative impacts of dam projects in other communities, were suspicious of the CFE’s promises of a rosy future. Others in the community pointed out that a much smaller dam built just below Paso de la Reina in 1992 devastated local fishing in the brackish waters abundant with a diversity of fish by creating a barrier between the river and the ocean. (See video: http://pasodelareina.org/blog/2013/07/16/que-pasara-con-nuestro-rio/).

Having seen the negative impacts of a dam firsthand as well as in other communities, concerned residents decided to get more information. They contacted Services for an Alternative Education (EDUCA), a Oaxacan non-governmental organizations known for their work in indigenous and environmental rights and the defense of territories, and invited them to present their information and experiences to residents of Paso de la Reina and other local communities in community forums.

Those wary of the Paso de la Reina had their concerns about false promises and negative impacts confirmed during EDUCA’s community forums. The thousands of jobs that CFE engineers had promised, for example, were illusory. Building and operating a hydroelectric dam mostly requires workers with technical skills, including operating heavy equipment – skills that campesinos and fishermen don’t possess.

And the livelihoods of most people in the region that would be impacted by the dam project come from agriculture – and much of their rich farmlands would be lost with the proposed project.

Another detail that the engineers failed to mention, but that was revealed in documents acquired by EDUCA, was that a smaller dam below Paso de la Reina was also in the project’s plans. That omission effectively avoided the fact that the entire community of Paso de la Reina would disappear under water.

“We’ve learned over the six years that we started to organize that the government’s and transnationals’ plan is to begin with this megaproject, with the idea of eventually owning one day all that belongs to us,” said Senovio Chávez Quiroz, former Municipal President of Paso de la Reina and an outspoken member of COPUDEVER.

During the festivities women several women community leaders addressed the crowd, pointing out the importance of their participation in the struggle. “As one compañera said, we have a voice and a vote. I think the time has come when women have awakened and are using their voices, saying ‘I’m here. I’m also in this struggle to defend life. I’m going to defend the life of nature, of the environment, because as a woman I also create life’,” said Eva Castellanos Mendoza. “So I think that women have played a very important role in this struggle. They are using their voices, and when they decide that they are going to do something, well, they do it.”

During the July event at El Zanate, local priest Padre José Guadalupe gave a mass celebrating the anniversary of the blockade. “We give thanks to God that people here have been struggling to defend for four years what in good faith and consciousness we all must defend. And while it hasn’t been easy, with the ongoing threats and intimidation, nevertheless you are here constantly maintaining the blockade – and always nonviolently,” Father Guadalupe said. “I’ve seen people have grown in their awareness that their land is something sacred, something that gives them life. The land is a blessing that we have to nurture and something that we can’t let be lost. It is, in the end, what sustains us and what will sustain your children.”

“In spite of the attempts to create divisions, there are people in COPUDEVER from a variety of political parties that are actively participating and resisting because they share a common goal – the nonviolent struggle to defend their lands,” he explained.

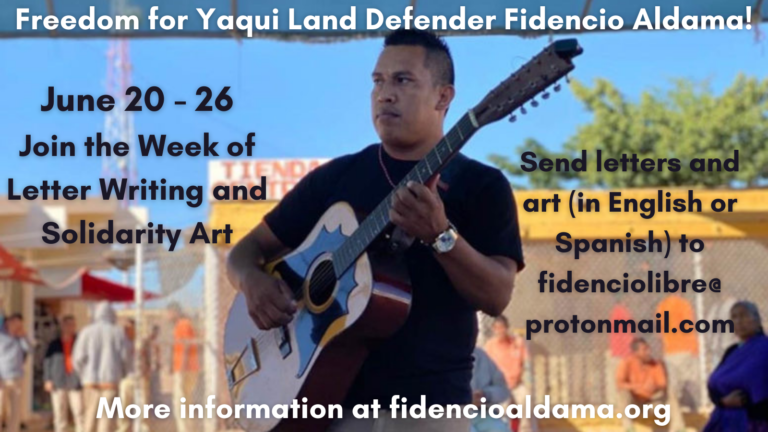

Several people pointed out that their struggle against the Paso de la Reina hydroelectric project is just one example of many struggle of peoples to their territories. And they spoke of the importance of building alliances with other struggles against mega development projects – not only locally, but also on national and international levels.

Jonathan Treat is a journalist, professor, activist and founding member of the non-profit organization, University Services and Knowledge Networks of Oaxaca (SURCO, A.C.) www.surcooaxaca.org. Treat leads SURCO delegations related to defense of territories in Oaxaca and Chiapas. He is a frequent contributor to the CIP Americas Program.

Sources:

1) “Informe Público, Paso de la Reina”, Servicios para una Educación Alternativa (EDUCA)

2) “En Rio Verde, Oaxaca, otra batalla por el agua”, La Jornada, July 17, 2013

3) http://pasodelareina.org/blog/2013/07/16/que-Pasara-con-nuestro-rio/

4) Personal interviews, “El Zanate”, Paso de la Reina, July 11, 2013

5) Laboratorio Multimedia para la Ciencias Sociales, UNAM

For more information:

Recent report published by EDUCA (in Spanish): http://pasodelareina.org/blog/2013/07/16/informe-publico-paso-de-la-reina/#sthash.wjUQEAjb.dpuf

Websites:

Videos:

“¿Qué Pasará con Nuestro Río?”

“Comunidades de la costa de Oaxaca en defensa del Río Verde”

English translation of a communiqué from EDUCA about the dire situation on the coast as a result of torrential rains and flooding. At least 40 homes in Paso de la Reyna alone have been flooded.

Paso de la Reyna, standing and organizing for humanitarian aid — PARTICIPATE

Residents of Paso de la Reyna are standing, working and organizing themselves. The community, through its own efforts, is carrying out “tequios” (unpaid community works and service) — cleaning up (after the flood) and a team of young people left this Monday to obtain food and supplies in the municipal center of Santiago Jamiltepec, and had food for the community today. They have re-established electricity and telephone service, but potable water is scarce. The municipal president and the Comisiariado Ejidal (head of the community commons) left for the municipal center of Jamiltepec to report on the damages done by the flooding, the municipality has been declared a disaster zone. Compañera Julia Herrera of the Diocese Commission today is organizing a caravan to bring food and other humanitarian aid to Paso de la Reyna. Compañera Leonor Díaz in Tututepec is coordinating storage facilities for humanitarian donations. We are currently monitoring other communities and municipalities that are members of the Council of Peoples United in Defense of the Rio Verde (COPUDEVER), but don´t yet have news, especially from San Antonio Río Verde, Ixtayutla and Tataltepec.

ACT: To contact the humanitarian storage center about donations en the coastal region: Humanitarian Aid Center, Santa Rosa de Lima. Casa de Tere Cordero. Tel: (52) Country Code 954 543 8000. For information from Leonor of the Diocese Commission, Tel: (52) 954 559 1460. For information from Paso de la Reina, Hugo Gómez, Tel. (52) 954 962 2629. COPUDEVER is arranging a bank account number to receive cash deposits for humanitarian aid, tomorrow we will have those details.