Originally published to It’s Going Down

Translated by Scott Campbell

Download and Listen Here

This is a special IGDCAST with Sofi, an anarchist compañera from Mexico City who is deeply involved in a variety of solidarity and organizing efforts with anarchist prisoners in Mexico. The audio interview is in Spanish, while below is an English transcription, along with two song MP3s you can download separately. If you want to see more in depth reporting on what is happening in Mexico, be sure to support our Mexico trip fundraiser.

We start off this episode with a recorded greeting from the Cimarrón Collective in North Prison in Mexico City. Then Sofi discusses the persecution and repression facing the anarchist movement in Mexico City as well as a review of the situation of four anarchist prisoners currently being held by the Mexican state. We look at the corruption, exploitation and neglect that occurs in Mexican prisons and what compañeros on the inside are doing to fight back. In particular, there is a focus on the Cimarrón Collective, a formation started by anarchist prisoner Fernando Bárcenas that has autonomously reclaimed space inside the North Prison and self-manages a variety of initiatives. For listeners, perhaps the most intriguing one will be their punk band, Commando Cimarrón. A couple of their songs are included in the podcast.

The interview then wraps up with discussion of a proposed amnesty for prisoners being put forward by “leftist” political parties in the Mexico City government and the response of our anarchist compañeros. Lastly, there are suggestions for how the struggle for their freedom can be supported from outside of Mexico. Throughout this post, we include links for more information, primarily in English, and photos of some of the art produced during workshops organized by the Cimarrón Collective.

IGD: First, we’re going to listen to a greeting from the Cimarrón Collective from the North Prison in Mexico City.

Cimarrón: Greetings and good afternoon. We are Commando Cimarrón, transmitting live for Sofi in the U.S. We’re sending our greetings and want you to know that the compañeros are doing well. This is a writing dedicated to all the compañeros up there who are prisoners, for all those who have lost their freedom because of capitalism, because of oppression, because of the state of domination.

We are a wild animal and domesticated beings bore us. It’s true that this domesticated planet bores the wild and the free. And it’s also true that many lambs like to go around disguised as wolves, jotting down in their notebooks about the abominations of humanity. Hahaha. Trying to influence others. But they are cowards for not doing it themselves. They’re all talk and like to pretend it’s real. But it is only real for a few. Don’t be deceived, don’t believe their pretty words. Recognize the wolf by its teeth and not by its sounds, so as to not fall again into their traps of the “modern jail” or their defense of social welfare.

No to the imposition of the state!

No to the criminalization of poverty!

Yes to the cimarrónes!

Yes to Commando Cimarrón from the North Prison!

Yes to the strike!

Yes to freedom!

Thank you, Sofi. To the subversive comrades in the U.S. from the walled city, Commando Cimarrón.

– Hard.

IGD: And now we’ll continue with the interview. Hi Sofi, thanks for being with us. Would you like to say a few words of introduction?

Sofi: Hello and thank you very much for the invitation. I’m not a part of, but I work in coordination with the Anarchist Black Cross in Mexico and I work with other compañeras and compañeros in an individual manner. I don’t belong to any collective, but it’s a network of individuals who have taken on the responsibility of freedom for our compañeros.

Repression of Anarchists in Mexico City

IGD: Great. And welcome. Can you tell us a bit about the situation of anarchist prisoners in Mexico?

Sofi: Yes, the situation is very complicated. Now we have four anarchist compañeros detained in Mexico. Their circumstances are very difficult because, as is worth mentioning, the Mexico City government for years has strongly persecuted the anarchist movement on many levels.

They’ve attacked social organizing spaces, such as the Che Guevara Auditorium, which is in University City that is part of UNAM [National Autonomous University of Mexico], a public university in Mexico City. And there is a space that was occupied by students in 1999 and over the years the ones who have taken responsibility for the space are anarchist compañerxs. It’s one of the points that have been attacked. A few weeks ago Chanti Ollin was evicted, an okupa that had been around for more than ten years, and there are also anarchist compañerxs involved.

On the other hand there has been the constant persecution of compañerxs, illegal arrests – well, arrests, because all arrests are illegal – and there has been a well-planned, constant series of arrests. There are also the smears in the media against the anarchist movement, like almost everywhere in the world, branding it as being just about violence, linking us with crime of terrorism according to the new world terrorism model. And they have also focused specifically on a few compañerxs, seeking to discredit them, which is very dangerous as they put photos of compañerxs in the media and this can lead to any person in the street attacking them.

It’s been an intense time, also an important time of resistance that I think has been well-organized. Not only on the defensive, but also on the offensive. I’m referring to the organizing of concrete anarchist spaces, such as the return of the Social Reconstruction Library in Mexico City, which is very important to us as it permits us to study anarchism and is a space for the public in general. Others work in community/independent/free media, strengthening our spaces, the Anarchist Black Cross continues. That is one I think all of us should look at, as it’s an initiative that has fulfilled its duties as being a consistent space of support for prisoners and they’ve done it very well for years. As I said, I don’t belong to this initiative, but I work in coordination with them as for me they are very trustworthy compañerxs.

That also means the state has taken a look at them as well and has been harassing several of them. Such as constant surveillance at their houses and what we call periodicazos – where one day you wake up and there’s an article about anarchists and identifying compañerxs as if they were terrorists. Yet the main work of the ABC is supporting prisoners, with others it’s media, and of course, if we’re facing down the state, well, then yes, we’re dangerous, but in reality there is nothing secretive like them claim about our political work, which is organizing ourselves publicly. We put in work on social issues and we’re not hiding a thing. But the state behaves as if we were, as if we were organizing terrorism. So there has been this constant period of smears, harassment, a few compañerxs have had their homes searched by police, scaring their relatives, interfering with our phones, etc.

Another part is the constant effort to arrest compañerxs for any reason. A common feature of the arrests is that many times they lead to nothing. They seek to paralyze people, because if you’ve got a case against you and if you do something they can arrest you again and they won’t let you out. So they seek to paralyze us, even though they don’t follow up on the charges. But often this doesn’t work, as for many compañerxs it just makes them angrier and gives them a stronger desire to fight.

It’s worth mentioning that of the most recent arrests, since the arrival of Enrique Peña Nieto to power as president, there have been three or four hundred illegal, constant arrests, with human rights violations. I don’t want to over-focus on the judicial-legal framing, but speaking in judicial-legal terms, there have been constant human rights violations. There is no respect for the legal process, they are all set ups, it’s obvious. There’s no evidence, the law in Mexico doesn’t exist, it’s completely non-existent. The clearest example of this for the world is the 43 disappeared. With this example, it shows clearly that in Mexico there is not justice, legality, true investigations, the judges and police are corrupt. The only thing that is clear is that in Mexico, the one thing that can give you justice is money. And we don’t have money. So we don’t have justice.

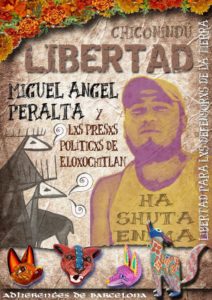

Miguel Ángel Peralta Betanzos

As I was saying, there are now three anarchist compañeros and one compañero with libertarian tendencies, who is Abraham Cortés, who are prisoners. In the state of Oaxaca, we have our compañero Miguel Ángel Peralta Betanzos. He is held in Cuicatlán prison and is from the community of Eloxochitlán de Magón, which is the community where Ricardo Flores Magón and his brothers Enrique and Jesús were born.

As I was saying, there are now three anarchist compañeros and one compañero with libertarian tendencies, who is Abraham Cortés, who are prisoners. In the state of Oaxaca, we have our compañero Miguel Ángel Peralta Betanzos. He is held in Cuicatlán prison and is from the community of Eloxochitlán de Magón, which is the community where Ricardo Flores Magón and his brothers Enrique and Jesús were born.

The community has an important history of anarchist struggle and Miguel Betanzos joined it. The struggle is for usos y costumbres [indigenous social and organizational practices] and to prevent the removal of natural resources from the community, etc. In Mexico, the matter of political parties is very complicated. There are political parties with strong criminal histories, such as the PRI. The PRI is one of the political parties inside of Eloxochitlán. Things are very tense in the community and it is split into two sides, the side with political parties and the side in favor of autonomy. Obviously the side that has the power of the government is the political party side. There have been intense attacks against those seeking autonomy, and among them is Miguel Ángel Peralta Betanzos. First, his father was arrested. Fortunately he is now free. Later they arrested eleven more compañeros belonging to the community assembly. And finally they arrested Miguel.

Miguel was arrested in Mexico City where his family has a small business. His was at the shop one day when the police arrived and removed him by force from his business without any arrest warrant or paperwork. They disappeared him for many hours, no one knew where he was. The car that took him had no license plates, there was no way to identify it. No one was notified until later. He was transferred to Oaxaca and they accused him of first-degree murder, for a murder that happened in Eloxochitlán while he wasn’t even there. Like we said, they’re set ups. You can say you weren’t there and the state says, “Yes, you were there” and you say, “No, but look, I wasn’t,” and they say, “No, you were, that’s that.”

They arrested him on April 30, 2015 and just a few days ago he had his first hearing, which was the “evidentiary hearing.” In quotation marks, because the police weren’t there, they’ve cancelled hearings, and more than a year after his arrest he hasn’t been sentenced, there’s been almost no movement in his case. This concerns us because he’s in a prison that is a new one-of-a-kind version in Mexico that they want to base all their prisons off of. It has been adapted from the United States, where the prisoners all wear uniforms, there is little contact with guards because everything is electronic, visits aren’t permitted, reading material isn’t allowed, they can barely go out to the yard, letters aren’t allowed, it’s very difficult for someone who isn’t related to visit, and this increases the isolation of our compañero.

We say in Miguel’s case that his crime is autonomy and social organization. We say that our compañeros are neither guilty nor innocent, because we also don’t want to be saying, “Our compañeros are innocent.” Our compañeros fight for social justice, they are anarchists, and of course they are fighting for a different society. So of course they are criminals under a judicial-legal system. What they are innocent of are the crimes they are accused of, but they are not legally innocent because they are fighting. I don’t want to get into this subject more. For what they’re accusing him of, he’s not guilty. Of fighting for social justice, he’s guilty.

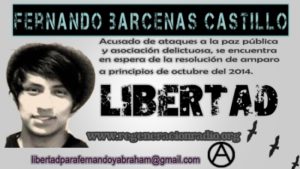

Fernando Bárcenas Castillo

We also have our compañero Fernando Bárcenas Castillo. He’s a 22-year-old young man. He was arrested on December 13, 2013. In Mexico City there’s a public transport called the metro. It’s the most widely used transport because it’s the relatively least expensive. When Miguel Ángel Mancera became mayor of Mexico City, one of his promises was to not raise the metro fare. He came into power and he raised it. So political activities began to condemn the increase and how the politicians keep lying. For many the price of the metro can seem petty, but for a worker who earns 75 pesos a day, paying for the metro is significant.

We also have our compañero Fernando Bárcenas Castillo. He’s a 22-year-old young man. He was arrested on December 13, 2013. In Mexico City there’s a public transport called the metro. It’s the most widely used transport because it’s the relatively least expensive. When Miguel Ángel Mancera became mayor of Mexico City, one of his promises was to not raise the metro fare. He came into power and he raised it. So political activities began to condemn the increase and how the politicians keep lying. For many the price of the metro can seem petty, but for a worker who earns 75 pesos a day, paying for the metro is significant.

During the first mobilization that happened on December 13, the Coca-Cola Christmas tree was burned and Fernando and two other young people were arrested. Fernando was an adult, he was 18, and the others were 17, so they sent those two to juvenile detention and Fernando to an adult prison. They released the two minors with probation and they had to go throw a psychological process for a year to “rehabilitate”. They brought charges against Fernando for attacks on the public peace with a gang enhancement/criminal association, because he was arrested with two others. The higher sentence is for criminal association and not for attacks on the public peace. Shortly I’ll explain why that matters.

Our compañero is the founder of a newspaper distributed in the prison he is at, the North Men’s Preventative Prison, but it’s also distributed in other prisons. Copies have made it to the U.S., Greece, Italy, France, of course it’s been translated in the different languages so the compañeros can read it. He is also part of a collective that develops the political and conscientization work Fernando is doing in prison.

A collective has been created called the Cimarrón Collective. They used cimarrón because cimarrón is an animal that was in a state of domestication and then returned to its wild state. The collective varies, sometimes there are seven, twelve, fifteen compañeros, sometimes less. This has been due to the consistent efforts of Fernando to organize inside of the prison. He’s the founder of the newspaper El Canero and also gives workshops on creative writing, film club, study circles, anarchism – of course – and among the projects the collective has is a punk band called Commando Cimarrón. Fernando is the guitar player, he writes some lyrics.

Corruption, Exploitation and Neglect in Prison

Fernando has been in consistent struggle and attack against the prison system. He’s constantly denouncing the conditions in the prison. There is no health care. Prisoners can die from simple illnesses, such as diarrhea or a fever that can be easily cured. There is no real education. The prison Fernando is in is for social rehabilitation, but the prisoners don’t rehabilitate. The prisoners live in violence, it’s a violent system like almost all prisons in the world. Little by little they lose hope of readapting to society and little by little they learn to be more violent. Not because they’re violent, but because of the small society that develops in the prison. They’re always being humiliated and shamed.

Overcrowding is a big problem. In the prisons, a cell made for five or six prisoners can have 20 prisoners sleeping in it. The youngest many times sleep standing up, tying themselves to the bars, because there is no space to sleep. Imagine a young person, no matter how strong, their health declines rapidly. Many of them have to sleep on top of the latrine where they defecate and urinate, there is no space. The prisons are very dirty, they’re always exposed to skin infections from rats and cockroaches. Sometimes they get very severe skin infections. I don’t recall the name, but it’s a bacteria that can cause gangrene.

The health system is complicated in the prisons. For a pill for a fever one can wait all day in the clinic, the doctor arrives, and they don’t attend to you. We had a compañero who is fortunately out now, who had a bad toothache, and we all know that a toothache is one of the most intense pains one can have, and they didn’t do anything for him because they didn’t have the necessary supplies. So we asked what they needed, and said, “If what you’re lacking is are the supplies, we’ll bring them”. We got the supplies and brought it to the prison clinic so they could attend to our compañero. As we come from a platform of solidarity, we have the capacity to obtain tools and expensive items that families with few resources can’t afford. That’s an example of the health care.

The food is very bad, it can be rotting. The meat almost always makes them sick. There’s a food they call “radioactive egg”, because if you cook an egg, the egg is white and yellow. Well, this egg is green, so they call it “radioactive egg” and obviously they don’t eat it. Another thing the solidarity network does is try, within our means, to bring them food that they can prepare on the inside so they don’t necessarily have to eat the food the prison gives them. Sometimes we’re not able to and they have to eat that food, but we work so that this doesn’t happen.

There is also labor exploitation. So when prisoners went on strike here in the U.S., the compañeros immediately said, “Of course, we have to be in solidarity and make links with them.” They are also exploited. For example, in Oaxaca where Miguel Ángel Peralta is, a soccer ball – to make it, sew it, and sell it to a company like Nike and that are very expensive in stores – they are paid three or four pesos per ball, around 10 or 15 cents. If you’re fast, you can make two balls per day. If you’re slow, one.

There is also sexual exploitation. This is more prominent in women’s prisons. We don’t work in women’s prisons because we don’t have direct connections with any compañera who is in one. If there were a compañera prisoner, of course we would have those connections. We don’t enter using institutional means, we visit as relatives. Because I’m not going to ask the institution to give me permission to do a workshop. Not because they wouldn’t give it, but because I want to do it all in an autonomous and self-managed way. This reduces the possibilities we have of entering other prisons, but we don’t want to strengthen the position of authority, so that authority can say, “Look, I gave them permission to enter.” No, we don’t want anything to do with the state. But we know about the exploitation of compañeras because it’s known, the people know about it, but nothing is done about it.

Corruption is also an issue. For relatives who want to visit prisoners, they charge you. You may think it’s not much, like five pesos, but… For example, you enter and give them your ID. And if a guard thinks your ID has something about it that he considers off, he can say, “No, you can’t enter.” “You can’t enter” means that you have to give him five pesos. You have two options, argue with him or give him five pesos and enter. Almost everyone pays because the visit with relatives is more important than arguing with a guard. Next you go to the clothing review. Women aren’t allowed to have metal in their bras, you can’t wear certain colors. And if they tell you there that you can’t enter, you pay again. And in that manner you pass through a series of points where you have to pay. Many kinds of food aren’t allowed in, so you have to pay. It’s a constant corruption. So if 1,000 relatives enter on visiting day, and they’re charging each five pesos several times, we’re talking about a large sum of money the authorities are getting. One family can end up spending a lot of money for one visit, so for a relative to visit a prisoner gets complicated.

It’s these types of things that Fernando has been speaking out against through statements and hunger strikes. Fernando has gone on four hunger strikes. For 12 days, 25 days, 56 days and 14 days. This has put his health at risk. The last strike was to condemn the entire prison system and also in solidarity with the prisoners in the United States. The compañeros (Abraham Cortés, Fernando Sotelo and Fernando Bárcenas) stopped the strike mainly because if Fernando Bárcenas didn’t stop, he would’ve had serious complications with his pancreas and liver. He now has complications with his stomach and kidneys. He’s very underweight and hasn’t been able to gain the weight back. So we also have to take care of this.

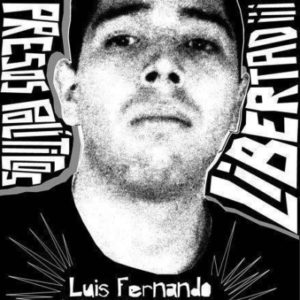

Luis Fernando Sotelo Zambrano

We also have another Fernando, Fernando Sotelo Zambrano. He was arrested on November 5, 2014 during actions in solidarity with Ayotzinapa and the 43 disappeared. And without evidence or anything, our compañero was sentenced to 33 years in prison [After this interview was conducted, Sotelo’s sentence was reduced to 13 years]. The only evidence is because a cop saw him. But in his first statement, he says, “I think I recognize him.” In the second, “Well, I think I recognize him more.” And in the third, “Yes, it was him.” But in reality we’re talking about the statements of someone who isn’t even sure if he saw him. So they arrested our compañero. 33 years and five months in prison, a fine of 519,815 pesos which is about $25,000 USD more or less, and payment for damages of 9 million pesos, which is about $400,000 USD. An amount that we’ll never be able to pay. But that’s not all.

We also have another Fernando, Fernando Sotelo Zambrano. He was arrested on November 5, 2014 during actions in solidarity with Ayotzinapa and the 43 disappeared. And without evidence or anything, our compañero was sentenced to 33 years in prison [After this interview was conducted, Sotelo’s sentence was reduced to 13 years]. The only evidence is because a cop saw him. But in his first statement, he says, “I think I recognize him.” In the second, “Well, I think I recognize him more.” And in the third, “Yes, it was him.” But in reality we’re talking about the statements of someone who isn’t even sure if he saw him. So they arrested our compañero. 33 years and five months in prison, a fine of 519,815 pesos which is about $25,000 USD more or less, and payment for damages of 9 million pesos, which is about $400,000 USD. An amount that we’ll never be able to pay. But that’s not all.

Why the fine? Because a Mexico City transport bus, the Metrobus, was burned. This transit system is “public” but in reality the concession is held by a private company, so the fine isn’t even going to Mexico City but to a private company. The bus was burned, the compañero was detained and the fine and everything is for the damage to the Metrobus. And the Mexico City government together with the owners of the Metrobus said, “No, that sentence is too low,” and they appealed and they want him to get a higher sentence. So right now the appeal is in process. We see this as part of the policy that we talked about at the beginning, of making life hard for anarchists who are in the struggle.

Fernando Sotelo is part of the Other Campaign, which is a Zapatista movement. He is also part of the Ollin Meztli student collective. He’s always putting in work, participating in Zapatismo, in the Che Guevara Auditorium. He’s politically active, young. That’s also important to mention, the constant attack on the youth.

Abraham Cortés Ávila

The other case is Abraham Cortés Ávila, a youth from the city of Oaxaca who was arrested on October 2, 2013 in Mexico City during a march commemorating the massacre of thousands of students on October 2, 1968 in Mexico City. Every year there is a march, lifting up the student struggles in the city. And on that occasion Abraham wasn’t planning on going to the march. He’s an artisan and he went to buy some things in the city center for his work. He saw the march and said, “Of course I’ll join because it’s important.”

The other case is Abraham Cortés Ávila, a youth from the city of Oaxaca who was arrested on October 2, 2013 in Mexico City during a march commemorating the massacre of thousands of students on October 2, 1968 in Mexico City. Every year there is a march, lifting up the student struggles in the city. And on that occasion Abraham wasn’t planning on going to the march. He’s an artisan and he went to buy some things in the city center for his work. He saw the march and said, “Of course I’ll join because it’s important.”

He joined the march and was with the compañeros and at a certain point the police attacked the mobilization. When the police came towards Abraham, the first thing he did was grab a plastic water bottle and instinctively threw it at the police and ran. The evidence against Abraham is an image edited by Televisa, a massive media company in Mexico City. It’s of Abraham throwing the water bottle, they cut away, and the next image is of a Molotov landing on a cop and setting him on fire. Though it’s obvious that what Abraham is throwing is a water bottle while the next clip is a Molotov burning a cop. That’s the evidence.

First he was sentenced to more than 12 years, but after an appeal his sentence was reduced to a little more than six years for attempted murder, for trying to kill a cop, something that isn’t true. He’s also part of the Cimarrón Collective. He gives workshops on handicrafts, drawing, he boxes on the inside.

These are our anarchist compas who are currently prisoners, arrested in Mexico City and Oaxaca. In Mexico there are more than 500 political prisoners. Many times their names aren’t known. We know more or less who they are. But all are inside for fighting for life. Defending their natural resources, defending their work, education, autonomous security, their people, autonomy, etc. Basically all are there for fighting for survival, for a dignified, important life of struggle. Of course we call for the freedom of all our compañeros. We’re abolitionists. But our work is focused on anarchists, which is why we are talking about them and not about others. Not because they’re not important, but because our work is in the prisons with our anarchist compañeros, since we are anarchists.

The Work of the Cimarrón Collective

IGD: Thank you, Sofi. And as you said, the Cimarrón Collective has a punk band inside the North Prison. Now we’re going to take a musical break and listen to one of their songs, called “Enajenación” [Alienation]. Download the song here.

IGD: Can you talk to us a little more about Cimarrón and what they do, what does it look like and how do they do it?

Sofi: OK. Cimarrón, like I told you, is a collective of male prisoners – since they’re in a men’s prisons. Following the logic of Fernando about doing social work inside the prisons. Look, something I like a lot about Fernando is that he doesn’t see prison as a burden. He says, “We as anarchists can do work in society, whatever society we find ourselves in. Right now, I’m in prison and I’m going to do work here.” He doesn’t see prison as weighing him down, he sees it as an opportunity to do anarchist politics in the prisons.

Coming from this framework, Fernando has made a lot of connections with other prisoners. He worked with some and that’s when the first hunger strikes started, forming CIPRE, which is the Informal Coordinator of Prisoners in Resistance. Thanks to the CIPRE, some so-called social/common prisoners were released, though every prisoner is a political prisoner, through pressure brought by CIPRE. Later CIPRE dissolved, and Fernando formed Cimarrón Collective with other compañeros.

Cimarrón Collective has a more cultural than political aspect. Its work with prisoners involves workshops, softening up a little the weight that unfortunately political work carries. They use culture as a means of conscientization. The prison has its workshops, its culture, and all that. Teachers come from the outside to give workshops. So they said, “If we know how to do things, why don’t we give workshops?” So they started scheduling their workshops, and one says, “I know about tattooing, so I’m going to give a workshop on that.” Another says, “I know how to draw.” One compañero, Sinué Rafúl, paints with oils and he offers an oil painting workshop. Another does drawing. Fernando offers, like we said, workshops on creative writing, study circles, film club. Abraham does handicrafts. Another compa, Ramón, does yoga. Gerardo Ramírez does tattoos and painting. A variety of them give different workshops. I give one on collective creative writing.

Soon we’re going to have two projects coming up. One is health promotion, so that prisoners have the ability to examine other prisoners and help with simple illnesses, such as colds, gastritis, headaches, using acupuncture and natural medicine like tinctures. What we’re doing is something very simple. Someone trains me and I train others. And if a prisoner has a more specific illness, there is a solidarity group of doctors on the outside that offers support. They are compañeros who are adherents to the Other Campaign, who were prisoners from Atenco in 2006. There are general practitioners and specialists, nutritionists, psychologists, all are involved in the social movement.

That means that the prisoners are going to get care in some way when they have specific issues, such as the compañero with the toothache. Or when Fernando, after the last hunger strike, was being transferred and during transport the guards beat him and broke his jaw. It was broken for eight months, and with political pressure we were able to get our dentist compañero inside to see him. The prison didn’t want to provide any supplies, so we had to bring in everything to create a mini dentist’s office in the prison so that Fernando could be taken care of. There are compañeros who are specialists in chiropractic, acupuncture, and they help.

The other is on communication and community radio. We’re giving workshops on speech, program structure. They are starting to write their scripts, deciding what they want to discuss, and soon, there will be a radio show and you all can listen to it. Well, in Spanish, of course. I really like it because we work a lot on reappropriating language. They have a language in the prison and we tell them that they don’t have to try to speak any other way, use your own prison language.

There is also an anarchist library called Xosé Tarrio, who was imprisoned in FIES (special isolation) prisons in Spain. He was known as an escape artist, he was always trying to escape, so he was considered one of the five most dangerous prisoners in Spain. He died of HIV in very bad conditions. His mom, Pastora González, says, “My son died from prison, not from AIDS.” So the compañeros recognize the efforts of Xosé Tarrio and put his name on the library. The library is public, any prisoner can use it. Most of it is anarchist texts but there are other readings.

Another one of their projects is the punk band, Commando Cimarrón. Some write the lyrics, others compose the music, others play the bass, the guitar, the drums. You’ve heard one of their songs.

And there is a pamphlet, a zine, they put out called Wild and Criminal. The cover has a drawing done by Fernando Bárcenas. And each of the compañeros, on every Thursday for six months, put together this work. It was designed and published by the Anarchist Black Cross. And editing was done by compañerxs Luna and Belarmino Fernández and me. But it wasn’t a strict editing, more a proposed style that they had to be really comfortable with. Sometimes they said no, other times they accepted the edits. We don’t want to carry the idea that it has to be perfect writing. What interests us is what the compañeros write.

The workshop has the intention of creating memory through the individual and through that memory we can create collectivity. And it’s been a great workshop for them. At the beginning they said they didn’t know how to write, always thinking that writing is for professionals. And we said that’s not true, we can all write. We did some simple exercises to help them start. And they noticed they could write easily. They liked it a lot because they said it created an emotional catharsis.

An example that I’m never going to forget. We were in the workshop and they have to sign in three times a day so the guards know they haven’t escaped. There’s a sign-in at 3pm, more or less during the workshop. So they have to leave the workshop and sign in, and then return. One time, one of them was writing, super focused, and another prisoner said, “Hey, wanna go sign in?” and he turned around and said, “What?” And he told him, “Yeah, we’re going to sign in. Are you coming or not?” And he turns around and says, “Ah, I’m in prison!” And he turned to me and said, “Sofi, I’d left prison!” For me it was really powerful, because writing helps them, in certain moments, to leave prison.

Another thing that is important to mention is that they live in a male society. The society is patriarchal and doesn’t allow them to feel sad, they always have to be strong and macho and good, they should never be sad, because that represents weakness. In the workshop they’re allowed to say, “I feel really bad.” And they’re allowed to cry. Which for many people is a simple action, but for them it’s not simple. When they read their work, their voice cuts off and they cry, it’s very gratifying for them. That’s the catharsis that allows them to understand themselves as individuals. And that allows for the creation of collectivities. It’s this work that very simple but has a social impact for them, not for anyone else, for them. That’s Wild and Criminal, it’s also in Spanish.

I want to read you something short that they put out. I’m going to read something by Hard that’s from an exercise we did. We said, “If cimarrón is an animal, whichever animal that returns to its wild state, what animal do you identify with?” And we’ll write about the animal you identify with. Hard identified with the hummingbird.

In the Cimarrón project, we are everything, painting, music, death, our imagination is our best quality. In Commando, Project Cimarrón, I am a hummingbird that flaps a lot, a lot, its heart catches fire, just as my heart catches fire; to fly is my trait, why do I want feet if I have wings to fly, said Frida Kahlo. This hummingbird that flaps in your heart, shows you the smile of fire, that your heart burns, burns much like the flapping of the incredible hummingbird. I am the hummingbird that greets you with a burning heart.

With each day, with each flap, to the left and to the left side, to the cold, to the summer, to the moon, to the sun, to all our stars: I am the hummingbird.

The hummingbird that flaps colors on its wings, the hummingbird on the left side of conscience.

We can see that it’s a poetic work, not so simple. On the radio program that you’ll listen to soon, hopefully, it’s very interesting because they use sounds really well. It lets the listener understand more what it’s like living in prison. You’ll like it a lot. That’s Wild and Criminal, the prison anthology, there are approximately 43 texts. I’m very proud of this work, not because I was involved, but because of what it represents for them. After this, I see them being more human and less like the criminal charges that the Judeo-Christian state tags them with and the idea that they should live in bad conditions because they deserve it. Now they are compañeros who are becoming more dignified, smiling more, their bodies aren’t as hunched over, they stand more erect, certain aspects of them have changed. And that for me is very important.

There is also El Canero, the newspaper that they all work on. It is more political. Any prisoner can write, anonymously or not, condemning the prison system or their case. Other political and anarchist prisoners have written for it. Those are the projects that Cimarrón Collective does. And it’s in a space that the prison didn’t provide, it is a space they’ve created autonomously. The library, everything is created and maintained autonomously. But it is very much supported by the community. They invited us to a concert they put on, and I really liked it because many prisoners came and they started requesting songs. Their songs are becoming known in the prison. So it’s less like their own project, many prisoners are familiar with it and we’ve gotten to meet a lot of them.

I feel very safe with them. There’s always this idea that entering a prison is dangerous. That’s not true. Of course the prison imposes danger. I can say that one of the places I feel safest and among friends is with them. I know that they’re not going to try anything. Another prisoner isn’t going to try anything because all my compañeros are there who take care of me, and we take care of each other. They’ve learned to see women not like machos from the Mexican machista tradition but they see us as anarchist compañeras. I don’t like the word respect, but with some form of respect. It’s not that they respect me, it’s that they identify with me as a compañera.

That is more or less the work of the collective and the collective was born thanks to the work of Fernando Bárcenas, the constant, ant-like work. And today we received some very bad news, which is that Fernando’s last legal recourse, which is judicial injunction asking the judge to analyze the case, and if he granted the injunction it would have resulted in a new sentence, meaning that, practically, Fernando would have been released after paying bail. But they denied the injunction today, after nearly a year of waiting. This means our compañero will be in prison for another three years. This Tuesday [December 13], marks three years imprisonment for Fernando. So he has another three years, as he has a sentence of six years.

We don’t know what the next legal step will be. There are other possibilities, like bringing it to the Inter-American Human Rights Court or the Supreme Court. It’s very difficult to bring those cases, but, we’ll keep you informed through the compañeros here and we’ll stay alert. Fernando doesn’t place any faith in the law, so this ruling isn’t so severe for him. But it is for his mom. It’s going to be a strong blow to her. And to us as well. Of course we want our compañero free. But Fernando is a strong young man. He’s clear on why he’s inside and he’s clear that the struggle is not for his freedom. The struggle is for the transformation of society, a free one, more just, more human, more autonomous. That’s the situation. This year we’ve received two pieces of bad news: the 33 years in prison for Fernando Sotelo was also a tough blow for us and now the denial of Fernando’s injunction. But, well, to fight, then.

Government Amnesty for Anarchist Prisoners

IGD: For me it’s interesting to see how for decades now the Mexico City government has supposedly been leftist, but it hates anarchists and is always repressing them. But now, some are proposing the idea of amnesty, obviously without consulting the prisoners involved. Can you tell us a little about what’s happening with this idea of amnesty?

Sofi: Yes, well, it’s true that they’re always attacking not just anarchists but all social movements. Its supposed leftism is even more hypocritical, then. I think that the PRD [the ruling party in Mexico City] lost a lot of social support since Mancera came into power with the fare increase in the metro, with the Metrobuses, with the gentrification happening in the city. It’s trying to gain support with social sectors that interest them, that can generate votes.

We all know the issue of prisoners is a very human one, to release prisoners is also a way of seeking social reconciliation with social movements. I think that the PRD and MORENA and other supposedly left parties are looking to regain this support for the next elections. What could be better than to free prisoners? Prisoners who they can say are young, under attack, vulnerable. Rather than a dedication to the left, it’s a move to generate support and votes. Of course, none of our compas agree with it. And like you said, it’s true, they haven’t consulted with the prisoners.

In spite of this, some of the families, it’s important to mention, are interested in amnesty. For example, Fernando Bárcenas’ mom. It’s very complicated, because videos have been released where Fernando’s mom talks about his case to Amnesty International. This is a complicated matter between Fernando and his mom. As a mother, she is seeking freedom for her son. But as an anarchist prisoner, he doesn’t want amnesty. She is looking for anyway to obtain her son’s freedom and I think she’s going to do this more now that they’ve denied the injunction. But Fernando doesn’t want amnesty, because amnesty in one way is saying, “I forgive you” for your crimes and I’m reconciling with you and you can go free. Fernando, like the rest of the prisoners, is saying, “What do they have to forgive me for?” He doesn’t want it.

Fernando Sotelo also doesn’t want it. Abraham Cortés doesn’t either. There is also Alejandro Jamspa, who is among the prisoners who could go free with the amnesty and it appears to me that he does want it, but I’m not very sure because I’m not in contact with him. But the rest, no. They understand it’s a political maneuver so that any person could say, “Oh, it’s so great, the government released them, yes, the government is concerned about social issues.” And we know that’s a lie.

So it’s very complicated, and at some moments you’ll see things about amnesty for Fernando because of his mother’s efforts. Here, it’s been tough dealing with this issue, such as for the ABC, as individual anarchist compañeros, because we are completely in agreement with Fernando Bárcenas’ logic. But we also don’t want to tell his mom, “Don’t do it.” Because in the end, she’s gone from being a mom to being our compañera in the struggle. We’ll see how things go with the possibility of freedom for Fernando. He’s never going to be comfortable with amnesty. We’ll see if they take Fernando off the amnesty list. In the end, I think these political parties are going to ask for amnesty for Fernando even though he doesn’t want it. And if they give it to him, they’ll let him go. So he’ll be out, whether he likes it or not.

Support and Solidarity

IGD: My last question is, for those who speak Spanish or not, where can they go to learn more and what can they do from here in the United States to support the struggle there and to be in solidarity and make these connections in the anti-prison struggle?

Sofi: I think that the most important thing is spreading information about the compas’ cases. Doing that with the cases in a way puts the freedom of our compañeros on the national agenda, but also on the radar of every political collective and individual. Things like this interview, what you’re doing is very important, because it’s not only going to be in Spanish but also English. People can also visit the website abajolosmuros.org, which is the Anarchist Black Cross website. The updates about our compañeros can be found there. Or on Facebook, Libre Fernando Sotelo, Libertad a Miguel Ángel Peralta or Fernando Bárcenas, each one has their Facebook page. But I think a page where you can find trustworthy information about prisoners is the Anarchist Black Cross – Mexico site. You can also email the ABC or birikota [at] riseup [dot] net. You can send greetings or letters there.

It’s very important to write to the prisoners. It helps them feel accompanied, in organization and coordination with others. We know it’s hard to write a letter, you don’t know who they are, don’t know what to say, but I’ve seen the faces of our compañeros when they’ve received a letter, even though it may just say, “Hi, how are you? My name is such and such. I want you to know that I’m with you and fighting for your freedom.” Something small. It makes them very happy. Also you can begin an exchange of letters with them through the emails I’ve mentioned. We can help send letters back and forth, because if you write directly to the prison, it’s not going to get to them.

So one is spreading the word, another is contacting them directly, and another is financial. It’s necessary and important, but it’s not the most important. In the end, we’ll be able to get economic support through many means, but if someone wants to help the families, you can also contact us at the same emails and we’ll go over different ways to provide economic support. I think these are the most important, so that if something comes up you’ll know, a campaign or something, you can join from where you are. I don’t know, visiting the Mexican consulates, putting out an image on social media, simple things.

The important thing is that the cause of our compañeros keeps cycling through. Above all, it’s being in touch with them. For them, a letter is very important, sometimes more important than financial support. Of course our compañeros here are going to be an important source. It’s one source, they are always attentive to translating texts from our compañeros. Both in Spanish and English, they translate a lot and they’re going to help us with translating this interview and we’re very grateful for that. And the compas send many greetings. They’re pleased that word about them is spreading in the United States. So, write them!

IGD: Is there anything else you’d like to say or didn’t mention?

Sofi: I don’t think so. I think we touched on everything in a general way. Above all, thank you for the space and spreading information. A call to pay attention to our compas’ legal proceedings, not just them but all our compas. Here in the U.S. there are tons of prisoners. I know little about prisoners in the U.S., that’s why it’s important to always be informing ourselves. I think it’s the responsibility of all to join in the struggle for our prisoners’ freedom. It should be one of the main issues we’re working on. Thanks for the space. The compas send their greetings to all those hearts that are open to receive this information and this struggle for the freedom of our compañeros. Thank you.

Download another song by Commando Cimarrón here.