by carolina saldaña

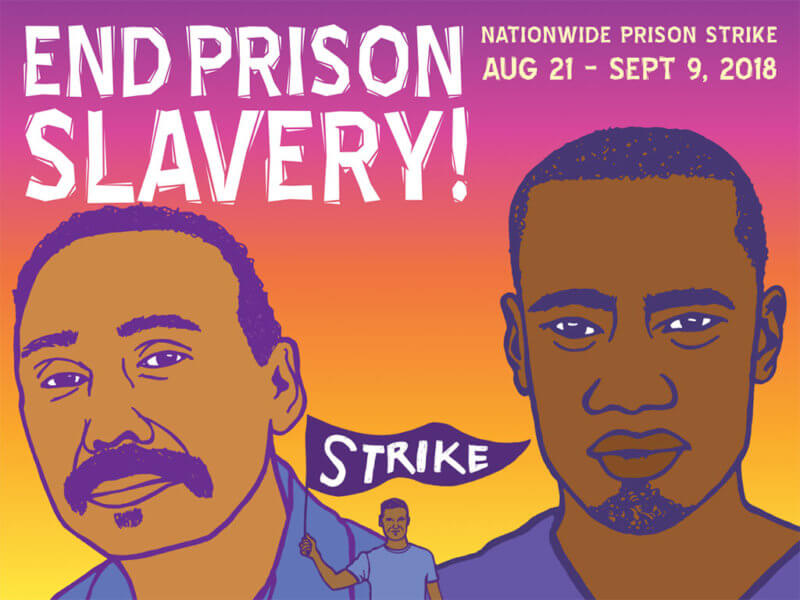

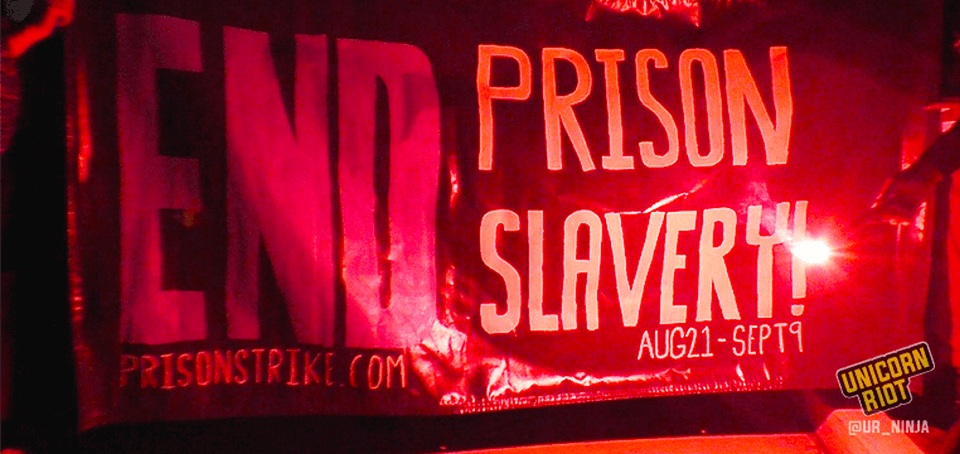

The Nationwide Prison Strike throughout the United States began on August 21, 2018, the anniversary of the assassination of George Jackson in San Quentin Prison in California and ended on September 9th, 47 years after the rebellion in Attica prison, NY. Two historic dates in the revolutionary movement inside the country’s prisons.

On July 17th of this year, the artist, analyst and organizer Kevin ‘Rashid’ Johnson, of the New Afrikan Black Panther Party, wrote an article that places this strike in the context of several years of resistance in the prisons of Texas, Georgia, Alabama, California and Florida as of 2010. Rashid argues that a new movement is on the rise against slavery and the inhuman conditions in prisons, which is eroding the structures of isolation imposed almost half a century ago to put an end to the prison movement that existed in the 60s and 70s.

During the Nationwide Prison Strike of 2018, there were actions in at least 36 institutions in 17 states.

On September 13th, the results were announced by Amani Sawari, the outside spokesperson for the collective, Jailhouse Lawyers Speak, JLS, which offers legal advice and resources to other prisoners and has played a key role in the coalition of prisoners that organized the Nationwide Prison Strike 2018.

In her remarks that congratulated all the collectives and individuals who helped make this mobilization a great success, the spokesperson stated that under the leadership of the prisoners themselves, it was possible to bring together the organizational efforts of hundreds of groups and individuals in different parts of the country, call the attention of an important part of the public to the intolerable prison conditions, and begin to put the basic demands of the strike on the national agenda.

Among the sources of invaluable information are the National Black Newspaper San Francisco Bay View, the anarchist web page It’s Going Down, and the incarcerated workers page IWOC.

Reports on actions continue to be reported despite difficulties in communication, abuse of striking prisoners, and statements of prison officials who say no strike went on in their prisons. This happened in Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, New York and South Carolina, among other states. “There are no strikes occurring in Georgia,” wrote Department of Corrections spokesperson Joan Heath, in a typical statement.

In the streets…

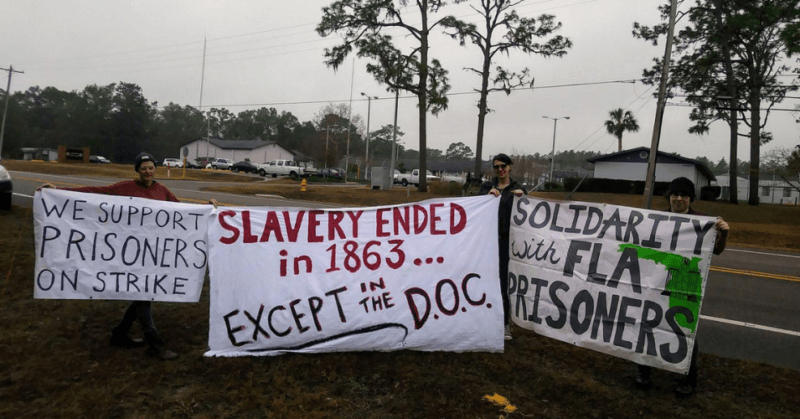

Outside the prisons, the International Workers Organizing Committee, IWOC, and local groups organized solidarity actions in at least 21 cities on or before August 21st.

During the 20 days of the strike in August and September, JLS reports at least 100 noise demos, marches, rallies, film screenings, forums, seminars and nights for hanging banners, putting up graffiti, creating different forms of art, and writing letters. At times when prisoners faced repression, phone zaps were organized to defend them. The solidarity actions were truly impressive. One rally outside the San Quentin prison in California, for example, drew almost 500 activists.

At times, actions took place outside the same prisons where prisoners were involved in the strike, and in other cases, they were held outside other prisons or in key places. At one noise demo outside the Metropolitan Correction Center in New York City, for example, people saw hundreds of lights blinking in the hands of prisoners inside.

In the world…

Internationally, prisoners in the Burnside jail in Halifax, Nova Scotia in Canada were among the first to identify with the demands of the strike and hold a solidarity protest to demand treatment as human beings.

In Greece, 127 prisoners in the Larissa prison hung a banner and sent a solidarity message.

And the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) sent a communiqué citing the common motives of this strike and their own struggle in Israeli jails for the liberation of their land and people from colonialism and occupation. They express their high esteem for George Jackson, “a true voice of struggle,” and note that after he was killed, the poems of Palestinian poet Samih al-Qasem were found in his cell. They send greetings to the imprisoned strugglers of the Black Liberation Movement, including Mumia Abu-Jamal, “whose internationalism and principled struggle is known and resonates throughout the world.” They demand his freedom and that of political prisoners Leonard Peltier and Mutulu Shakur, among others.

What unleashed the Nationwide Prison Strike of 2018?

The strike originally planned for 2019, began after a battle on April 16th in the Lee Corrections Institute in South Carolina, in which at least seven prisoners died, six of which were African-Americans.

The spokesperson of the Free South Carolina Movement, Efia Nwangaza, said at a demonstration outside the prison: “These men lost their lives and many more were permanently injured due to prison mismanagement, irresponsible leadership, untrained officers and staff, and the warehousing and stockpiling of humans due to mass incarceration and over-sentencing designed to create a volatile prison culture.”

Their demands include a policy of zero tolerance for “racism, sexism or any form of oppression or inhuman treatment.”

According to IWOC member Cole Dorsey, when prisons are used as warehouses, all the problems behind bars are multiplied. Somebody who works for years for 13 or 18 cents an hour loses hope, especially when there are no opportunities to study or receive training necessary to find a good job after getting out of prison. With his cell phone, the former prisoner has helped with communications among different organizers inside and outside of the prisons. Cole voiced special appreciation for the support provided by the San Francisco Bay View, which has disseminated the goals and actions of the national strike in newspapers sent by mail to hundreds of prisoners, who, in turn, spread the news to their friends.

Amani Sawari confirmed that it’s true that the battle described in the media as “gang related” did involve people from different street organizations, but what has almost never been said in the media is that the conflict was instigated by the guards. They took away the lockers from one group of prisoners, then assigned those prisoners to live in cells occupied by other groups, knowing that there would be fights. The deaths of the prisoners could have been avoided, “had the prison not been so overcrowded from the greed wrought by mass incarceration, and a lack of respect for human life that is embedded in our nation’s penal ideology,” said the JLS spokesperson.

She added that due to the volatile situation after the battle, many prisoners in different parts of the country felt that they couldn’t wait to act. They reached an agreement on ten basic demands.

The Demands

- Immediate improvements to the conditions of prisons and prison policies that recognize the humanity of imprisoned men and women.

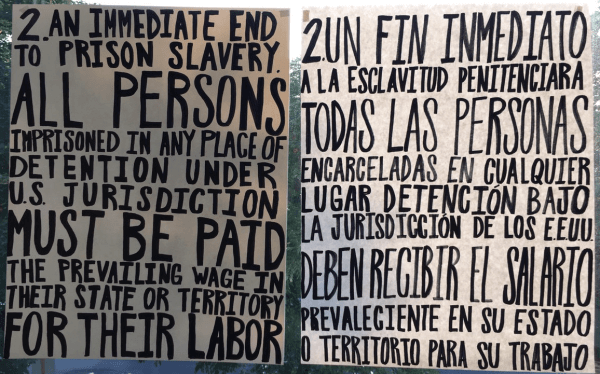

- An immediate end to prison slavery. All persons imprisoned in any place of detention under United States jurisdiction must be paid the prevailing wage in their state or territory for their labor.

- The Prison Litigation Reform Act must be rescinded, allowing imprisoned humans a proper channel to address grievances and violations of their rights.

- The Truth in Sentencing Act and the Sentencing Reform Act must be rescinded so that imprisoned humans have a possibility of rehabilitation and parole. No human

shall be sentenced to Death by Incarceration or serve any sentence without the possibility of parole. - An immediate end to the racial overcharging, over-sentencing, and parole denials of Black and Brown humans. Black human beings shall no longer be denied parole because the victim of the crime was white, which is a particular problem in southern states.

- An immediate end to racist gang enhancement laws targeting Black and Brown human beings.

- No imprisoned human being shall be denied access to rehabilitation programs at their place of detention because of their label as a violent offender.

- State prisons must be funded specifically to offer more rehabilitation services.

- Pell grants must be reinstated in all US states and territories.

- The voting rights of all confined citizens serving prison sentences, pretrial detainees, and so-called “ex-felons” must be counted. Representation is demanded. All voices count.

Calling for the strike…

On April 24, 2018, JLS called on prisoners in all parts of the country to participate in the national strike that would be held based on the agreed upon demands, utilizing work strikes, hunger strikes, sit-ins and boycotts of phone calls and items sold in commissaries, depending on the situation in each prison. People on the outside were also convoked to help with communications, protest actions and the dissemination of demands.

The organizing groups also expressed their support for the Redistribute the Pain campaign that had successfully begun on Februrary 1, 2018.

Its goals and tactics were laid out by Bennu Hannibal Ra-Sun, formerly known as Melvin Ray, one of the main spokespersons of the Free Alabama Movement along with Kinetic Justice (Robert Earl Council) before and during the National Strike 2016. Let’s don’t forget that the two organizers, among others, were harshly punished and transferred to the dangerous prisons of Kilby, Limestone and Donaldson, where they have spent many years in isolation. Despite all that, they continue to resist.

Redistribute the Pain

In speaking of the campaign Redistribute the Pain, Bennu Hannibal said:

On January 21, 2018, our loved elder, revolutionary leader and teacher Hon. Richard ‘Mafundi’ Lake joined the Ancestors…

Let his transition serve as yet another lesson to us of the immediacy of our situation behind these walls and serve as a reminder of why we can’t wait to commit our all to the struggle to end slavery in America. We are, without any doubt, still slaves and chattel here in America for no reason other than the color of our skin…

We are four months into a one-year bi-monthly… boycott campaign against collect phone calls, commissary/snack line/store draw, incentive packages or visitation vending machines. Our objective is to defund prison systems by disrupting departmental operating budgets by removing these funds from government budgets and redirecting these funds towards building a national organization whose agenda and purpose will be to end mass incarceration and prison slavery.

These redirected funds will help generate and disseminate educational material and books on mass incarceration, prison slavery and the 13th Amendment; help incarcerated freedom fighters publish books, articles, poems, arts and crafts, and other material needed to fund our movement; help to develop an e-business platform to centralize funding; and, among other things, help finance development of our own app so that we can consolidate and organize all of our movement information into one click of a button. We can never be an independence movement if we don’t establish an independent structure.

What actions went on in the prisons?

During the Nationwide Prison Strike 2018, prisoners participated in different ways. In some cases, only one or two people acted, while in others, dozens or hundreds joined in the mobilization. Even before August 21st, there were protests in some prisons. The states that stand out for the sheer number of people involved were Florida, South Carolina and Washington. Why?

In Alabama, on August 21st, Swift Justice told Al-Jazeera that prisoners in his prison were not showing up for work.

In Arizona, several prisoners sent there from Nevada began a hunger strike on August 21st.

In California, in Folsom state prison, a hunger strike was initiated on August 21st by Heriberto García, who recorded on his cell phone his refusal to accept food. When he found out what the menu was, he said: “Burritos or not, not eating today. I’m hunger striking right now.”

In another action, a group of prisoners engaged in a hunger strike in Lancastar prison.

In Colorado, around 20 inmates in the Sterling prison began to act at the beginning of August, before the 21st, when they went on hunger strike with demands against solitary confinement, the punishment of a group for the action of one person, and the lack of educational programs, among others.

In Florida, an article published on August 23rd in The Guardian reported strikes in 11 prisons, and one week later work strikes and boycotts were confirmed in Charlotte, Dade, Holmes, Appalachee, and Franklin prisons. According to reports from prisoners, at Charlotte, 40 prisoners refused to work and 100 boycotted the canteen. At Dade, between 30 and 40 were on strike, at Franklin between 30 and 60, at Holmes 70 participated, and at Appalachee an unknown number. Why so many? Did it have to do with the large number of prisoners already participating in Operation Push?

In Georgia, work strikes and boycotts have gone on in Reidsville and Jackson prisons. It’s important to note that in the work strike against prison slavery initiated in Reidsville in 2010, which spread to prisons across the state, the repression was especially cruel, including attacks on the prisoners with hammers that left some comrades unrecognizable.

In Indiana, prisoners in the Wabash Valley solitary confinement unit began a hunger strike on Monday, August 27, to demand good food and an end to cold temperatures in their unit.

In Kentucky, a boycott was confirmed in the federal prison at Manchester.

In Maryland, a group of prisoners refused to work in Jessup prison.

In Michigan, a group of prisoners in Alger prison boycotted all telephone contact and payments to Global Tel Link.

In Missouri, at least one prisoner was on hunger strike in the federal prison at Leavenworth.

At Polk prison, at least one prisoner was punished for going on hunger strike.

In New Mexico, the tension was so heavy in three units of the private prison in Lea County funded by the GEO corporation that the prisoners found it impossible to wait until August 21st to act. On August 9th, they went on hunger strike due to fewer family visits, harassment of families during visits and strip searches of older family members, as well as the harassment and abuse of inmates. In response, the Department of Corrections imposed a ‘lockdown’, in 11 prisons throughout the state on August 20th. Question: Will the situation in private prisons always be less tolerable?

In New York, there was a strike in Coxsackie prison and a work strike and boycotts in the Eastern Correctional Facility.

In North Carolina, around a 100 prisoners protested with banners that said “In Solidarity”, “Parole”, and “Better food”, while a demonstration of supporters went on outside the Hyde prison in the town of Swanquarter.

In South Carolina, work strikes and boycotts have been confirmed in Broad River, Lee, McCormick, Kershaw and Lieber prisons. A boycott also went on in the federal prison at Edgefield. Question: Were all of these actions already planned before the massacre in Lee prison, or were they a response to the repression?

In Ohio, authorities in Lucasville prison denied Siddique Hasan the right to phone calls and prohibited any communication with people outside prison about the Nationwide Prison Strike 2018. His response was to go on a hunger strike. Prisoners report that the authorities went so far as to sandbag his cell so that he couldn’t send or receive messages and information. The political prisoner has been on death row in Ohio since the Lucasville rebellion in 1993 and helped to organize the 2016 national prison strike.

Also in Ohio, prisoners in at least one cell block of the supermax prison in Youngstown participated in a fast during the first three days of the strike and in a commissary boicot during the whole strike.

In the Toledo prison, at least two prisoners, David Easley and James Ward, began a hunger strike on August 21st in solidarity with the national demands and in protest of the violence of the guards and a lack of health care. The authorities sent them to solitary confinement and cut off their communications with people outside the prison, but word has leaked out that after discontinuing it for a few days, they have resumed the strike and are engaging in it even after September 9th.

In Texas, comrade Keith ‘Malik’ Washington, Deputy Chairman of the New Afrikan Black Panther Party and member of IWOC, was sent to McConnell prison in the town of Beeville, where some prisoners participated in a work strike. The reprisals against him began on August 15th, when he was put in solitary confinement. In his concrete cell with soot on the walls, temperatures rose to 110 degrees Farenheit. He was not allowed to shower and couldn’t talk on the telephone. He went on hunger strike in his cell. “I’m fully awake. Are you?” he asked.

Jason Walker, in Telford prison, was put in solitary confinement in July, when he wrote an article on inhuman conditions in Texas prisons. The member of the New Afrikan Black Panther Party also suffered reprisals for his help in organizing the Nationwide Prison Strike 2018. He was not allowed to shower, have clean clothes, towels or toilet paper. He went on a hunger strike in his cell.

Robert Uvalle, who has been in solitary for 25 years, went on a hunger strike in Michael prison, where other prisoners also refused to eat.

In Stiles prison, near the Gulf Coast, two prisoners in solitary confinement went on a hunger strike in solidarity with the national action. On August 23rd, one of them sent a message to IWOC: “I feel great. But very hungry! And not because I don’t have food but because of our 48 hour solidarity with our brothers and sisters. It’s the only way we can show support from inside of Seg. Let everyone know we got their backs.”

In Virginia, a group of prisoners in Sussex II sent a communiqué that announced two 24-hour fasts each. The text published in Conscious Prisoner said that during these days they would be engaged in studying, training, and organization in memory of Jonathan and George Jackson, in the spirit of the prisoners who rose up in Áttica, NY; the prisoners killed in Lee prison, South Carolina, and their comrade John Trans, killed by Sussex II guards who showed a gross disregard for human life. In their greeting sent out to all freedom fighters, they called on them to keep on doing damage to the post-plantation slave system.

In the state of Washington, immigrants jailed in the Tacoma Detention Center went on three hunger strikes in 2018 alone. On August 21st, more than 200 prisoners joined in the national mobilization with a hunger strike and a work strike. They demanded that ICE centers be shut down along with an end to the separation of children from their families and an end to arrests and deportations. Question: Can this strong participation pave the way for more mutual resistance among prison abolitionists and people outraged by ICE policies?

Two more responses to the reprisals

Ronald Brooks, of Decarcerate Louisiana, organized a work strike in the notorious Angola prison last May and was helping to organize the Nationwide Prison Strike 2018. With his smuggled cell phone he had recorded a Facebook video in which a prisoner says: “We are anti-slavery and are organizing to transform our ghettos into communities and our jails and prisons into places of human redemption.”

At the end of June, Ronald was moved to the ‘David Wade’ Correction Center, a prison even worse than Angola, according to some observers. It’s hard for his family to visit him there and his mother has condemned his transfer as a reprisal for the organization he was doing. It didn´t surprise her that her son began to denounce the conditions in David Wade. “The thing about Ronald … even though he’s incarcerated, he’s always concerned about what he can do to help the conditions,” she said.

Kevin ‘Rashid’ Johnson had planned to participate in the Nationwide Prison Strike 2018 in Florida, where he had helped to organize actions for Operation Push since January 15th.

In retaliation for this, last June 12th he was returned to Red Onion prison in Virginia, “the original scene of criminal abuse.” Upon arrival, he was assigned to the “torture unit” that he had denounced in 2010. He said: “Except for me the entire 22 cell B-3 cellblock is empty, and since I’ve been in this pod I’ve been, unlike any other ROSP prisoner, denied all showers and out-of-cell exercise.”

But Rashid didn’t stay there long. On July 10th, he was moved to the maximum security prison Sussex II, in Waverly, Virginia, where he was put on death row even though he has never been sentenced to death. In an article of his published in The Guardian on August 23rd, he said he would be participating in a commissary boycott, doing what he could to inform people about prison slavery and supporting prisoners on strike. He says: “I may be locked up in solitary confinement, but I stand with the men and women rejecting modern slavery in America.”

What does JLS have to say about its analysis, demands and options for acting?

In the middle of August, Jared Ware, of Shadowproof, interviewed a member of Jailhouse Lawyers Speak, who wished to remain anonymous due to the search for organizers of the Nationwide Strike 2018 and the repression against them. Among other things, they spoke about prison slavery, social control, and the demands and options for acting in the strike. Below are a few excerpts from the interview:

JW: Talking a little bit about prison slavery, there are various analyses of that concept. … there are people who will really argue—including prison reformers and prison abolitionists—that prisons are not the same as slavery, but are a form of social control. What’s your analysis of all this?

JLS: Well, I think actually both of them are correct. They’re a mechanism of social control and they’re also slavery.

I have to say this here, from a New Afrikan perspective—and I have to say it like that, right?—because many of us back here, particularly from JLS, we come from different cultural perspectives, but from a New Afrikan perspective: I’ve always been taught…that the current prison system… comes directly from the plantation days.

Ever since Africans got off the ships…that connection has been clearly defined… I can remember my great granddaddy and them, they were talking about it. Prison is slavery. They never really referred to it as prison or as jail, they referred to it as being forced back onto the plantations again. This is something we’ve always understood. Of course, as things evolved more, the system evolved, it’s a little more sophisticated, and you know people tried to change the language and there was a disconnect.

I notice there’s a disconnect with a lot of our caucasian comrades… The continuation [of slavery], they haven’t experienced that. So they wouldn’t see it like that.

On the other hand, I think a lot of times people think when we say it’s slavery, that we miss the bigger picture that it’s also a mechanism of social control. We also understand that. We understand it’s a mechanism of social control, we understand the connections to capitalism, we understand how this enterprise has spread it around the globe today… But I think we do a grave injustice when we just ignore the fact that it’s still a continuation of slavery.

JW: I see that the demands that you all have issued are more comprehensive, and people can look at them from I think various walks of life, whether they’re radical or they just generally care about other human beings, and see that these are human rights issues that you all are organizing around…You also speak about other opportunities that people have to resist the prison industrial complex … I wanted to give you an opportunity to talk a little bit about the strategy behind that, as well as talking through some of those demands and opportunities for people to resist.

JLS: Well, when we were first talking to a number of prisoners in a number of different locations, and the guys were reporting back, we were trying to decide about these national demands. At first we had probably like thirty-something demands and we were trying to shorten down the list. We were trying to be fair with something that impacted us all. And we definitely considered it within the human rights realms.

One of the things we noticed when we had the last strike: a lot of people didn’t feel that they had the opportunity to participate. This was something that we noticed; for instance, they [were saying,] “all of us don’t work.” Some of us, like myself, we were on lock-up during that time period. Some people were in these lockdown units. They did not work, a lot of prisoners don’t have jobs, so there is no working for them, so there’s no way they can participate or feel a part of something that’s moving forward.

We had two or three guys on our calls that were a part of work release facilities or pre-release facilities. They wanted to know, what can they tell the guys because there is no way these guys are going to give up their positions for a strike, but they’d like to participate…

What happens when a prison is locked down? How can those guys [on lockdown] still participate? The boycott is on-point for those conditions. … One of the things we decided to do was boycott, and I think that brother Bennu [Hannibal Ra-Sun of the Free Alabama Movement], he came up with that right there through Redistribute the Pain. We went over that again and again, and that seemed to line up and it specifically still targeted the system, and it specifically still undermines the economics, because at the end of the day we have to figure out how to undermine the economics of the system, as well.

The sit-ins. Some of the prisoners wanted more aggressive action…We can verify at least two prisons right now where the guys want to sit in.

And then there was the hunger strike. It was for guys that were in the position that I’ve been in before, which was on lockdown. They can participate by refusing to eat that particular day and show their solidarity and resist. Because this particular stage between August the 21st and through September, it’s about showing solidarity with each other…

So by giving more options we had more participation.

New proposals

The success of the Nationwide Prison Strike 2018 is a breath of fresh air for people who want to see a world without prisons. It’s especially encouraging at a time when there is opposition to prison policies that are increasingly heartless, as we have recently seen in the state of Pennsylvania with the prohibition of books and letters in the hands of prisoners and the proposal in New York to have tele-visits instead of visits from human beings. While Trump pushes for private prisons, there’s opposition to the privatization of health care in many prisons. At the same time, prisoners who had achieved the release of hundreds of prisoners from solitary confinement in California are now resisting the non-compliance of accords that limited this form of torture. As the KKK and neo-nazi groups try to legitimize the white supremacy that’s always existed in the country, Antifa and some human rights groups confront them. In this context, a success won by any opposing group empowers other groups seeking emancipation in the society and the abolition of prisons. The more communication among these groups, the better!

In a message sent on September 16th, the JLS spokesperson Amari Sawari invites everyone who supported the Nationwide Prison Strike 2018 to continue to collaborate with Jailhouse Lawyers Speak and other collectives and individuals that favor prisoner demands.

It is especially important to organize and participate in actions to support prisoners who are experiencing reprisals, including Imam Hasan, Kevin Rashid Johnson and Jason Walker.

It’s still important to disseminate the achievements of the strike and to report on actions now underway.

Actions slated for the coming year include another nationwide prison strike and a national march to launch the strike. JLS is also fostering the formation of a National Coalition to support prisoner initiatives and a fund to receive donations.

The resistance continues!

“In Alabama, on August 21st, Swift Justice told Al-Jazeera that prisoners in his prison were not showing up for work.”

You published a false comment.

Swift Justice