From Radio Zapatista and translated by Scott Campbell. Additional photos, along with audios, can be found with the original text.

Text, audios and photos by all of us.

We dreamed “that the patriarchy burned” and that it was possible to inhabit spaces free of cruelty. For a long time, we graffitied it, theorized it, protested for it, and proposed it. We then came to shout this dream in a territory free of femicides. Here we cried it and wailed it. Here we sang it, danced it, cared for it in this valley of organization and work. From December 26 – 29, 2019, the Zapatista women sheltered us in their collective and rebellious lap to clothe us in dignity inside the seedbed carrying the name of Commander Ramona, who died 14 years ago. Walking in her footprints, in those of Susana and of all the founding mothers of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, we arrived at this gathering that never should have been. Violence against women, the topic of discussion at this international gathering, should have decreased if the systemic conditions of parity and equity we enacted as a result of feminist debates were enough. But they aren’t. These autonomous and self-managed Zapatista rebel islands, that have multiplied in the past year, resist within a rough sea of generalized violence that led to 38,000 murders in 2019 in a Mexico that doesn’t work. That same violence impacts billions of people, particularly women, boys and girls, as explained by the some 4,000 women who came from 49 countries that also don’t work.

It is the morning of December 27. At the opening of the event, Commander Amada carries her baby on her back while she speaks for the Zapatistas to ask us what we have achieved since the previous event, held in March 2018, at this same caracol in Morelia, Whirlwind of Our Words, where – whether present or absent – we agreed to live and to fight. The exchange of glances among both nationals and internationals begins, worried about the accounts we are going to have to give. The Zapatista women have achieved this: their demands from 1994 turned into reality, spaces without cruelty and without femicides, without human trafficking, or pedophilia, or the sex trade, or corruption, or drug trafficking, or individualized competition, without self-victimization. Spaces free of capitalism. Without repression or disdain or displacement or exploitation. They set up kitchens, bathrooms, showers, laundry and clotheslines, gazebos, tarps, collective stores, collective dining areas, electricity, drinking water, water, scrubbers and soap for washing dishes, stages with microphones and sufficient speakers, trash where garbage is separated, allowing it to be reused or recycled, clinics, schools, sports fields. They made their own video and audio recordings with Las Tercias Compas and learned how to drive ambulances, stake bed trucks, pickup trucks, and cars. They carefully marked the places with cell phone signal and let us charge ours. They gave us a lesson in women’s full autonomy.

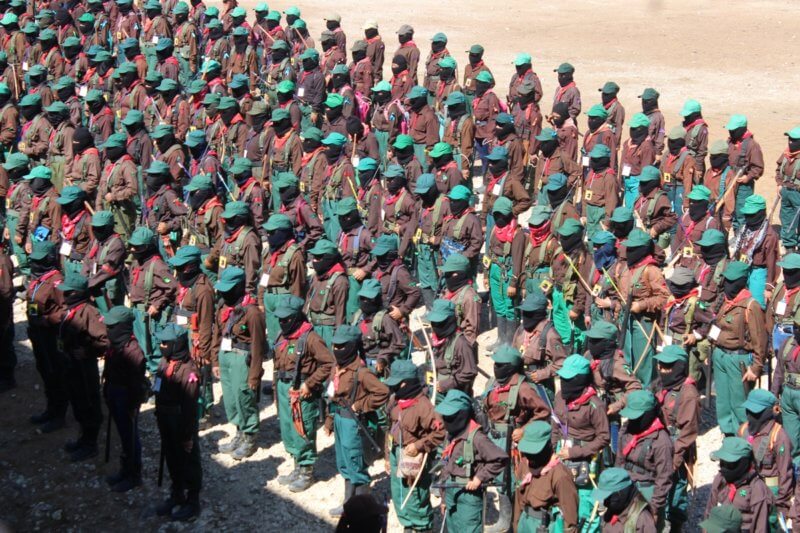

They then invited us to see their achievements, they registered us online without any external assistance, and they still asked for our critiques in order to improve. And now the time for the opening arrives. The Zapatistas present a performance that combines the strength and discipline of the militiawomen with the joy of a cumbia dance that makes us wonder, “what if this is love, what if this is love?” They are the daughters and granddaughters of those who put their bodies and lives into the uprising 26 years ago. Many come wearing bows and colored arrows and some without them. When the cumbia stops, the girl Esperanza [Hope] places herself in the center of the seedbed and expresses her need for help against violence. The militiawomen shout that they must protect her and they do. They run around her in concentric rows, forming a conch. Those armed with bow and arrow aim at the circular horizon while a thrice-given instruction asks them to “ready and aim” without firing. The nationals and internationals observe in silence. Esperanza is covered by us, surrounded and protected. Then they invite us up to the gazebo to take the microphone and share our stories of pain without holding anything back because, they tell us, these stories are going to stay here.

Around the seedbed which men are not permitted to enter, these militiawomen armed with bows and arrows will take care of us, be it under the sun or under a tender moon that is beginning to grow.

Day One: Word

It is difficult to bear the cascade of painful stories that bursts forth from the main gazebo, a cascade to which this first day is dedicated, but one day turns out not to be enough. More than 90 compañeras have asked to speak. Almost all of them tell us that it is the first time they have dared to recount their shame, their anger at the humiliation they lived. The silence, the weeping rage entwines us. Age, nationality, privilege or poverty matter not. The stories of each are the stories of all. Including of those who deny them or no longer remember them. And the power of the speakers, reflected back by the mountains, make the voices ricochet so as to be heard throughout the seedbed, at all hours, in every corner. For reasons that sociology has been unable to explain, many women are accustomed to going to the bathroom in pairs or groups. Hence, every walk to the toilets or showers is an opportunity for collective reflection.

That reflection will continue in the different dining areas, among them the “Women that We Are” or that of the “Compañera Militiawomen.” And each trip to the bathroom or dining area leads us to pause in our listening to say, “the same thing happened to me, a little different, but the same.” Because, in the testimonies of shaky voices and shouts, we all break a little remembering our teachers, or husbands, or bosses, or gods, or uncles, or strangers, or friends who humiliated us too often and for a long time. We recall our abortions, the vaginal infections, the beatings, the screaming, the brutal or “moderate” rape, the mocking laughter, the pressure to have sex without wanting to, the disappearance of a friend, her death, her murder. And we also recall our own acts of violence against other women, or against our daughters or sons. Enough. The few who believe themselves to be strong lie to themselves that it doesn’t hurt them, that it hasn’t happened to them, that it will never happen to them. It is too humiliating to acknowledge the way that capitalist patriarchy objectifies us. It’s too much humiliation.

Dozens of organizations of indigenous and campesina women are present, demonstrating the importance of this gathering and an example of the intersection of struggles of women from several countries who are defending territory, human rights, and women’s organizational processes. They are all coming from the Forum in Defense of Territory and Mother Earth that took place in the days prior in the new caracol of Jacinto Canek in San Cristóbal de las Casas. Cristina Bautista dreamed of coming to the gathering. She was killed two months ago in the Tacueyó massacre in the northern region of Cauca in Colombia. The funds that her compañeras from the CRIC (Cauca Regional Indigenous Council) had gathered for her trip were used to pay for her funeral. It was then that Women Spinning Feminist Thought organized a collection and were able to bring a small group from Colombia to the Zapatista seedbed, including Aída Quilcué [a prominent indigenous leader with the CRIC], who was finally able to hug María de Jesús Patricio (Marichuy). And so it was that the two gatherings came together. In the seedbed, a mural was painted with the image of Cristina accompanied by a militiawoman, very close to the other mural from which Ramona greets us. They say that here Cristina will be protected. That here she will remain in the memory of the Zapatista women. Here she will live.

On the microphone the voices reverberate non-stop. Voices of mothers without their daughters, of orphaned women, of the relatives of prisoners or those being persecuted, of girls from the city who name – for the first time – their harassers, their rapists, their brutes near and far. For millennia, women have learned to listen, perhaps to speak without being heard. Here, many women are learning to speak and to be heard. We have teachers instructing us, such as Araceli Osorio, the mother of Lesvy Berlín Osorio, murdered at UNAM; or Liliana Vázquez, widow with four children of Samir Flores Soberanes, from the People’s Front in Defense of the Land and Water Morelos-Puebla-Tlaxcala and the Amilcingo Resistance Assembly. We have the women from COPINH who speak for Berta Cáceres, or the women from Acteal who say what any poor and indigenous woman would say from any part of the world, among many others. There are also Black women reclaiming themselves as Black women, women from the LGBTTTI movement, hetero women, students, those who can’t read, elders, youths, girls, anarcha-feminists. Here they speak, and those who say they don’t know how to speak learn to speak while being heard.

When the moon shines dimly in the evening, the improvised songs and dances will begin, setting off a temporary healing. There are ancestral dances around small fires or songs with musicians who just met. Energized by the singing of Mon Laferte, the rappers immerse themselves in a cypher. It won’t stop for three days as Audry Funk, Obeja Negra, Batallones Femeninos, or Dayra create euphoria. Everywhere and for hours, others sing whatever brings us together, from La Bamba Zapatista to Selena, with the conviction that “everything changes,” ultimately arriving at the song we will carry in our throats: “Zapatista sister, your compañeras are here. Together we will win. Never, never abandon me in the struggle.”

Day Two: Respect

It’s December 28, and the Zapatista women give us complete freedom to organize the second day’s discussions. There are various workshops, such as self-defense, yoga, dance, healing and medicinal plants, or anything that someone proposes, including one on perreo [reggaeton dance] that made many uncomfortable and that many enjoyed. Alongside those, working groups gather around various themes: differently abled women, maternity, communication, art, textiles, workplace or family harassment, pedophilia, migration, obstetric and gynecological violence, education, health, travel, and abolitionism. This last group triggers patriarchal-type passions as it debates proposals on the prohibition of sex work, a prohibition that is not accepted by sex workers nor many feminists who, characteristically, fight against any imposition upon our bodies. In addition, the trans compañeras perceive discrimination from us and strongly condemn it.

Few groups reach agreements, almost all of them functional. But there is a binding element within the whirlwind of topics being discussed: respect. Whether it be that we demand it from those identified as attackers in the stories of pain or that we obtain it and work for it among ourselves, the majority of the debates occur in an environment that tries to follow the Zapatista model and seeks respectful ways to generate discussion, conscious that in order to demand respect, it must be given. This is how we listen to every group’s stories of sadness or happiness, respecting all emotions and experiences. “They killed my boy.” “They disappeared my daughter.” “They forced me to give my baby up for adoption and I’m looking for him. I need help to find him.” “I haven’t yet decided if I want to be a mother. I’ve come to listen to those who are mothers in order to decide.” “For me, motherhood is the deepest and most intense act of reciprocity between two people.” “I’ve come to imagine ways of not feeling alone when I fight against the capitalist system.” “We are a collective that proposes recognizing children as people with dignity and their own voice.” “Compañeras, we’re letting you know that we’re preparing a performance of ‘A Rapist in Your Path’ from the perspective and predicaments of disability.” “We need to bring the struggles of the academy and the teachers together with the students’ form of struggle.” “We need to set up a network of communicators who struggle.” “I don’t want to live in solitude anymore. “I no longer want to just survive.”

Throughout the day, many women spontaneously organize to support the Zapatista compañeras with cleaning the bathrooms or separating the garbage. Our hosts are perfectly organized and have arranged everything necessary for the work or the party to flow, but we are many and we are all busy with something. What remains is to share accounts of what has been achieved and to not let the light they gave us a year and a half ago go out. There is communication work, mini-meetings everywhere, clothes to wash, murals to paint, meeting notes to write, girls and boys who play, get lost, reappear, distract us or focus us. There are fabrics to embroider. There is flavored water, tea, coffee, pozol, chocolate, or mate to drink. There are pets to care for. There are Zapatista handicrafts to buy, materials from the insurgents, popsicles, popcorn, products made in order to cover the return trip. There are many Zapatistas to talk with, to smile with. There are many selfies to take. There is political and social information to exchange. There is analyzing to do. There is reading or writing. There is soccer or basketball to play. There is a lot of organizational coordination to strengthen. And all of this must be done while processing the collective pain of what was heard the day before without letting that pain end and preparing ourselves for what remains to be done. The weather is comradely, it treats us well. But the challenges that await us when we leave this seedbed seem unfathomable, in a country aiming for perfect patriarchy and in an extremely violent world. We will have to walk firmly in the footprints of Commander Ramona’s path in order to learn to respect ourselves just as this bastion of dignity respects us.

As night falls, indigenous butterflies arrive from Canada to move us with a dance. They are the Butterflies in Spirit, a group of women who won’t allow for murdered or disappeared indigenous women to be forgotten. As a prelude to the dance, they leave us raw while narrating their own stories of repeated sexual violence as they tell us, “You’ve now seen our faces and now know our names. It is your responsibility to find us and make us visible if one day someone disappears us.” Then begins a series of documentaries on violence against indigenous women in other latitudes. The rising moon aligns clearly with Venus. A transparent screen at the top of the gazebo allows for the films to be seen from many angles in the seedbed, while a fire dance gives way to many other massive dances that resound for hours in an atmosphere of joy and strength that nobody wants to, nor can, control.

Day Three: Life

December 29 arrives and the cultural events begin with the first rays of sun. Here, where the only woman’s blood that is spilled is our menstrual blood, many interrupt their breakfast upon hearing the call to quickly join a dance in the shape of a conch. The dance is to remember those who saw their dream of fulfilling the agreement to live cut short, it is to personify our compañeras who are gone, lights extinguished by institutional or misogynist violence. The conch grows out of control and soon there are dozens of women performing a dance that screams the pain of others and revives them among the bodies of those of us who are here. A compañera interrupts the performance to report that there is a lost child, and a commander reports that some have abused the freedom they have been given by consuming substances that are not allowed here. And so begins the last day that will be marked by the life, creation, art, music, theater, poetry, song, and dance of the women that we are.

Outside of the program, the compañeras from the differently abled working group will present their own version of “A Rapist in Your Path:” “And it wasn’t my fault if you didn’t listen, if you didn’t see. And it wasn’t my fault if I didn’t move like you wanted. The one who destroys is you.” On the formal program: Dancing We Resist (mass dance), We Love Ourselves Strongly (mass song), Sara Curruchich (music), Latin American Women’s Network, Kandyan (dance), Gypsy Theater, poetry by Liz Mirel, Paulina Rocha, Zi Hua, Maritere (music), At the Feet of La Malinche (reckless theater), Bharatanatyam (dance), Maruja Ambulante (entropy theater), Sisters (performance), Ana Lucía (music), Paola Jacinto (music), Where? (theater), Brave Woman (performance), Chicha the Calm (theater), One and the Sex (theater), Ana Ma (music), Marifer (music), Fire Show. On the informal program: “Open mic. Everyone welcome.” The closing of the gathering will be at 9pm Zapatista time. More performances organized on the fly shine with the sun’s final rays. “Dancing We Resist” and “A Rapist in Your Path” close out the afternoon.

To unite and not to divide. To speak and to no longer be silent. To listen and to come together in respect for the other that we all are. Those are the tacit agreements we’ve been making without writing them down in meeting notes. So, when the Zapatista compañeras ask us to pass around the microphone to read our agreements and conclusions, there are not many solid agreements to put forward. We return into their hands the proposals for the program, the initiatives, the details, what must be done to end the violence against us. We remain behind. There is a power outage and we haven’t reached an agreement. As such, proposals come forth for follow-up gatherings and reflections. The electricity returns when it is time for the closing. We come down from the gazebo in the heart of the seedbed. Commander Yésica takes the microphone and reads the first proposal, because the Zapatistas do have proposals.

The first proposal: “We all learn about the proposals made here and make our own proposals regarding violence against women and what we will to do stop this serious problem we have as women.” And to reaffirm how much everyone’s pain matters to them, the militiawomen repeat the action with the archers protecting Esperanza within the conch. The second proposal: “When any woman anywhere in the world, of any age and any color asks for help because she has been violently attacked, we respond to her call and find a way to support, protect, and defend her.” The third proposal: “All of the groups, collectives, and organizations of women who struggle who want to coordinate among ourselves to carry out joint actions, should exchange our communication information, whether that communication be by telephone or internet or however.” There are many forms it could take, they tell us, but they propose a joint action of women who struggle all over the world to take place “on March 8, 2020. And that everyone uses the color or symbol by which they identify themselves according to their own thought and way of doing things, but that all of us wear a black ribbon as a sign of our pain and sorrow for all of the disappeared and murdered women all over the world. This will be our way of saying to them, in every language, in every geography, and on every calendar: You are not alone. We feel your absence. You are missed. We will not forget you. We need you. Because we are women who struggle. And we will not give in, give up, or sell out.”

The first proposal: “We all learn about the proposals made here and make our own proposals regarding violence against women and what we will to do stop this serious problem we have as women.” And to reaffirm how much everyone’s pain matters to them, the militiawomen repeat the action with the archers protecting Esperanza within the conch. The second proposal: “When any woman anywhere in the world, of any age and any color asks for help because she has been violently attacked, we respond to her call and find a way to support, protect, and defend her.” The third proposal: “All of the groups, collectives, and organizations of women who struggle who want to coordinate among ourselves to carry out joint actions, should exchange our communication information, whether that communication be by telephone or internet or however.” There are many forms it could take, they tell us, but they propose a joint action of women who struggle all over the world to take place “on March 8, 2020. And that everyone uses the color or symbol by which they identify themselves according to their own thought and way of doing things, but that all of us wear a black ribbon as a sign of our pain and sorrow for all of the disappeared and murdered women all over the world. This will be our way of saying to them, in every language, in every geography, and on every calendar: You are not alone. We feel your absence. You are missed. We will not forget you. We need you. Because we are women who struggle. And we will not give in, give up, or sell out.”

With this commitment to life, with this respect and with this collective word, our gathering ends. “We have one year, sister and compañera, to move this work forward. Let’s not return here next year amidst the same violence against women without ideas or proposals for how to stop it,” they tell us. Here we were free for a few days. Here we were exactly the women that we are. For the children yet to come, or for the women and men who are no longer here, it will be up to all of us together to continue the dream of seeing this criminal system burn, learning from the past to forge and shape for ourselves, as women who struggle, the present and the future that we deserve.