Independent filmmaker Jill Freidberg (Granito de Arena, This is What Democracy Looks Like) provides a forceful rebuttal to a recent Seattle Times story in which travel writer Jolayne Houtz paints a woefully uninformed and misleading picture of the current political unrest in Oaxaca. Freidberg has travelled back and forth between Seattle and Oaxaca many times in the past several years, documenting social change movements and the current uprising. In her critique, she teases out how a seemingly innocuous travelogue can gloss over complex political realities, as Houtz blithely dismisses the determined motivations of local folks who have had the audacity to step out of Oaxaca’s beautiful scenery to demand justice.

Full Story:

To the editor of the Seattle Times, and staff reporter, Jolayne Houtz:

I am a Seattle-based documentary filmmaker. I spent three years in Oaxaca, Mexico, filming and producing the film, Granito de Arena, about a social movement of public schoolteachers who, for 25 years, have been fighting for social and economic justice in Mexico’s public schools. This year, I have spent most of my summer in Oaxaca, covering the current popular uprising that was the subject of the September 10th article, “What’s Wrong in Oaxaca,” published in the Travel section of the Seattle Times.

What’s wrong in Oaxaca? Over seventy years of crushing poverty, single-party rule, and institutional racism (Oaxaca is overwhelmingly indigenous) have left the majority of Oaxaca’s residents with few options outside of organized protest. What’s wrong in Oaxaca? Non-violent protestors have been beaten, disappeared, and killed. Their demands? The resignation of a corrupt governor who has spent public money in all the wrong places and carried out deadly repression against a non-violent movement with legitimate demands.

You began the article with the line: “Things turned desperate when the Coke ran out.” I implore you to look a little further into the situation that is evolving in Oaxaca. I’m sure you’d find that, for the people of Oaxaca, the Coke running out is the least of their worries. What’s happening in Oaxaca is a broad-based social movement responding to decades of social and economic injustice. In the four months since that movement took shape, people have been gunned down while participating in non-violent marches, and schoolteachers have been arrested and tortured, without ever having charges filed against them. They’re not worried about their Coca-cola running out.

I understand that you may feel it is the role of the Travel section to alert travelers to potential hazards in their vacation plans. However, the article “What’s Wrong in Oaxaca?” goes much further and reduces a historic moment in Mexico’s political history to nothing more than an inconvenience for American travelers. I found the article full of blatant inaccuracies and a clear lack of understanding of the political, social, and economic realities facing the state of Oaxaca in these difficult times.

I have included with this letter a paragraph-by-paragraph rebuttal to your article. I’m sure you won’t publish the rebuttal. All I ask is that you read it.

Jill Friedberg

*

What’s Wrong in Oaxaca?

by Jolayne Houtz, Seattle Times

Things turned desperate when the Coke ran out.

To put things in perspective, for the people of Oaxaca, things “turned desperate” when the governor of the state of Oaxaca sent 3,000 state police to attack an encampment of striking schoolteachers who were sleeping in the streets with their children, at dawn. “Things turned desperate” when, on August 10th, plain-clothed police opened fire on a non-violent march of over 20,000 people, killing Jose Jimenez Colmenares, father of two, mechanic, husband of a local schoolteacher.

We were among hundreds of travelers stranded at a palapa-roofed roadside restaurant southeast of Oaxaca last month. Protesters had barricaded a lonely stretch of the main highway between Oaxaca and the state of Chiapas to draw attention to a litany of complaints against the government. We missed getting past the barricade by 10 minutes.

Why does this article not delve into the “litany of complaints” that provoked the ongoing protests in Oaxaca, such as the fact that the governor of Oaxaca illegally spent millions of dollars from the state budget on his party’s presidential campaign; the devastating lack of state funding for basic public services like health and education; the long history of state repression against Oaxaca’s poor and indigenous populations?

Within hours, a local entrepreneur had launched a shuttle service, ferrying stranded motorists in his pickup truck to the makeshift barricade created by two commandeered buses parked lengthwise across the highway.

But walking past the barricade wasn’t an option for us. Our group of nine family and friends, traveling together in a two-vehicle caravan, was only halfway through what was supposed to be a six-hour trip from Oaxaca to Cintalapa, Chiapas.

We were now on Hour 11. The restaurant’s fresh shrimp and cold sodas that sustained us at the beginning of the blockade had long since run dry.

“I’ve had it. I’m going up there,” my husband muttered.

Twenty minutes later, Héctor, who is Mexican, and his brother managed to persuade protesters to open the road again.

If only Oaxaca’s deepening political crisis could be resolved so easily.

Center of tension

Oaxaca is the epicenter in an increasingly tense political conflict pitting thousands of teachers, students, farmers, activists and leftists against the government and police.

The protests began in May with a teachers strike, a comfortably predictable, annual event in which tens of thousands of teachers demand higher pay, negotiate with the government, proclaim victory with marginal raises and go home.

What this article fails to mention is why Oaxaca’s public schoolteachers go out on strike every year and what they demand when they go out on strike. For example, the typical Oaxacan schoolteacher earns about $600/month; works in schools with no teaching materials (no paper, books, pens, chalk, chalkboards, etc); pays for his/her own transportation to reach the communities where they teach; and often faces a classroom full of children from families so poor that the children have not eaten before coming to school. When the teachers went out on strike this year, their demands included: a cost of living adjustment, increased funding for school infrastructure, free school breakfasts, and free textbooks and uniforms for students.

But this year, things went wrong. State police moved in to break up the protests in June. Protesters said they were tear-gassed, beaten and jailed. They held their ground in Oaxaca’s pretty zocalo, or main square, and since have been joined by many other groups calling for the governor’s resignation.

“Protesters said they were tear-gassed, beaten, and jailed” implies that these claims are disputable. In fact, numerous state, national, and international human rights organizations documented the police attack on the teachers’ strike and confirmed that over 190 people were hospitalized as a result. There is ample media coverage of the event showing police helicopters firing tear gas and rubber bullets directly at protesters, from helicopters.

In July, the Oaxaca protests became a stage for protesters disputing the results of Mexico’s presidential election. Conservative Felipe Calderón was named president-elect last week after the nation’s top electoral court rejected allegations of fraud by his left-leaning challenger, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador. Lopez Obrador has refused to accept the court’s ruling and is considering naming himself head of a parallel government.

Oaxaca was never the stage for election-related protests. Protestors from across Mexico gathered in the nation’s capitol, Mexico City, to protest election fraud. Over a million people marched in the streets of Mexico City (the largest march in the country’s history) demanding a full recount of the vote. That recount never took place.

Three and a half months after the protests began in Oaxaca, at least two protesters have been killed, allegedly by rogue police officers.

Protesters have seized radio and TV stations to press their demands, and their leaders have begun talks with government negotiators aimed at ending the conflict.

Protesters have seized radio and TV stations because not a single media outlet in the state of Oaxaca allows a space for the people of Oaxaca to voice their concerns or articulate their needs. The only newspaper that dares to take a moderately critical stance of the government (Las Noticas de Oaxaca) has been attacked by armed gunmen three times since the current governor entered office. The community radio station run by the public schoolteachers was destroyed by police, on June 14th. The University radio station was also attacked by armed gunmen less than a month ago.

So far, soldiers and police have mostly kept their distance. But protesters and the city’s residents anxiously await the endgame, when they fear law enforcement will move in for a final, violent confrontation.

On August 22nd, convoys of uniformed, and plain-clothed, police drove through the streets of Oaxaca at night, and opened fire on peaceful protesters. One protestor, a public works employee, (Lorenzo San Pablo Cervantes) was shot several times, in the back, and later died in the hospital. Journalists who were following the caravan were also fired upon. The following day, the mainstream television network, Televisa, broadcast footage of the violence that clearly showed the gunmen to be uniformed state police. To say that police “have kept their distance,” is a blatant inaccuracy.

Church-group project

With that unrest as a backdrop, we were wary as we left for a two-week trip to the states of Oaxaca and Chiapas last month.

My husband and I were escorting a group of 26 people from Fauntleroy Church in West Seattle to Oaxaca to work on a construction project in a rural village several hours from Oaxaca city.

Most of our time would be spent in the village, where the biggest risks we faced were traveler’s diarrhea and sore muscles from digging trenches and hauling rocks for the foundation of the church we were building.

But we also planned several days in the capital at the beginning and end of our week in Oaxaca. More than half of our group were children and youth, many traveling without their families.

We’d been planning and fundraising for the trip for months, and no one was inclined to cancel.

But the news reports from Oaxaca were grim: Unruly anti-government protesters had taken over the city center. Streets had been closed and hotel windows smashed. Tourists were being hassled by protesters demanding their ID. And police had essentially abandoned the city.

There is not one documented case of tourists being “hassled” by protestors, nor being asked for ID. The protesters have made it clear that their complaints are directed at the state government, not at tourists.

Not the same

In fact, our experience in Oaxaca was quite different from the chaos we had read about at home.

We never felt unsafe, and we never were confronted by protesters. As a large group of Americans in a city now almost devoid of tourists, we certainly stood out. But we never drew unwelcome attention.

My husband and I comfortably walked throughout the city with our two young children. We allowed the youth in our group to walk in pairs around the city’s historic center.

We visited several key tourist destinations outside the city, including the ruins of Monte Albán and Mitla and weavers in the artisan village of Teotitlán del Valle. We traveled by bus and car throughout the state and found the unrest more of an inconvenience than a safety threat.

But the protests have left a visible, possibly permanent stain on one of Mexico’s most charming cities and provided an ever-present backdrop throughout our trip.

Over 70 years of crushing poverty, institutional racism, and single-party rule have left a “permanent stain” on rural Oaxaca. While, the social and economic injustices experienced by the majority of Oaxaca’s residents may not be evident in the downtown streets of “one of Mexico’s most charming cities,” it is these injustices that provoked thousands of Oaxacans to have take to the streets demanding the resignation of their governor.

Bus diverted

The first hint of the unrest came as we entered the city.

Our bus from Mexico City had to take a 15-minute detour to reach the bus station, teetering along a skinny hillside road to get around a roadblock erected on the main highway.

This inconvenient detour was not a result of the protests, but in fact the result of one of the many unsolicited “civic projects” imposed on the residents of Oaxaca City, by the state governor. Earlier this year, he launched a project to add an extra lane to the road that enters the city along the hillside that skirts the Cerro de Fortin. The project was initiated without any prior seismic testing, and resulted in massive landslides, which not only closed the road indefinitely, but also sent tons of mud and rock cascading down upon the neighborhoods below the road. The residents of those neighborhoods were among the first to join the movement calling for the resignation of state governor, Ulises Ruiz Ortiz. That road used to be the direct route to the bus station for all first-class buses arriving from Mexico City.

The closer we got to Oaxaca’s zocalo, the more apparent the problems became.

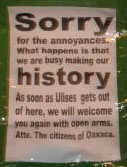

Graffiti and anti-government slogans were spray-painted on most buildings, much of it calling for the resignation of embattled Gov. Ulises Ruiz.

Some referred to the disputed presidential election or to international events. One showed the word “Bush” in a circle with a line through it, with the “h” in the shape of a swastika.

Close to the square, streets were blocked by chunks of concrete, the remains of burned tires and sheets of corrugated metal.

Oaxaca’s idyllic central plaza had been transformed into a tent city, its graceful gazebo barely visible under protest signs and blue tarps rigged between trees to provide cover from the sun and afternoon rains.

Businesses suffering

Tourists have virtually vanished from the city during what should be one of its busiest seasons.

Sidewalk cafes that normally would be packed with European and American tourists sat almost completely empty, waiters trading jokes to pass the time. The prominent Marques del Valle hotel on the square has been shuttered for three months because of the unrest.

Other large hotels have closed for lack of tourists. At our hotel, a small inn called La Casa de la Tia, we were the only guests.

“People are scared off by the press reports, so everyone canceled,” the hotel manager said.

Exactly. “Press reports,” such as this one, have scared off tourists. The tourists I have spoken with during my weeks in Oaxaca did not feel they were in danger, and many were actually glad to have the opportunity to witness such a historic moment. So, one wonders how much of the decrease in tourism is a direct result of the current situation in Oaxaca, and how much is a result of “press reports” that exaggerate the risk to tourists.

Business at a downtown women’s cooperative with more than a dozen rooms filled with highly coveted Oaxacan handicrafts is way off, perhaps 20 percent of normal, according to a shopkeeper who didn’t want to give her name.

“Some days we make not even a single sale,” she said. “All we can do is wait.”

During our visit, we never saw any law-enforcement presence in the city, apart from soldiers at the airport on the outskirts of town and private security guards protecting banks and money-exchange businesses.

Most shops and restaurants were open. Roaming vendors of hammocks and handicrafts worked the square and its handful of tourists, though with an air of resignation about what will be a difficult year for many in Oaxaca whose livelihoods are tied to tourism dollars.

No consensus

Many Mexicans have mixed feelings about the situation in Oaxaca.

One Oaxacan friend owns a pharmacy near downtown that she has had to close a number of times this summer due to protests.

She lamented that her son, just completing his medical residency, may not return to Oaxaca to start his medical practice because of concerns about the unrest and the region’s long-term stability.

“They’re pushing out the young people,” she said.

Outside the city, some have cheered the current governor when he has inaugurated new public works.

Others blame his government for political dirty tricks and the assassinations of unarmed opponents.

Some friends and relatives in Mexico grumble that protesters are overreaching with unreasonable demands and tactics that are hurting those they claim to represent.

Yet they also know protesters are voicing legitimate complaints from one of Mexico’s poorest states, where the gap between rich and poor remains vast and many have not benefited from Mexico’s strong economic growth.

My husband, too, seemed conflicted about the protests roiling his home country.

When Héctor and his brother marched to the blockade to have it out with protesters on our trip to Chiapas, they discovered the protesters were a handful of local farmers angry after the apparent police kidnapping of a protest leader from the area.

It’s likely that these local farmers weren’t just blocking the road because they were angry. They were carrying out a strategic action in an attempt to save one of the several movement “leaders” arrested, without charges, by state forces. On August 9th, schoolteacher German Mendoza Nube was in front of his house when he was pulled from his wheelchair by heavily-armed, plain-clothed thugs, and thrown into the back of an unmarked pick-up truck. It was believed that German, who is diabetic and on dialysis for kidney disease, was being transported out of Oaxaca City. Movement participants put out the call for people to block the roads leading in and out of Oaxaca, in an attempt to prevent German’s removal from the city. (German later turned up in a state prison). On August 11th, schoolteacher Erangelio Mendoza Gonzalez was arrested under similar conditions (plain-clothed police, unmarked car), and again movement participants called for blockades on the major highways leading out of the city, in the hope that Erangelio’s removal could be intercepted.

Héctor and his brother listened to the protesters’ complaints with a sympathetic ear.

And then they shared some of their complaints – some true, some not. We had a 1-year-old baby in the car who was vomiting, and we were out of diapers. (Not true.) We were tired, hungry and unable to explain to our children what purpose was being served by protesters preventing us from reaching our destination. (True.)

We drove past the protesters a half-hour later after they agreed to open the road for some 200 vehicles that had been stuck at the barricade. Héctor yelled amiably, “Suerte!” (Good luck!) and waved as we passed.

But when we reached a second blockade a few miles later that briefly held us up again, Héctor was feeling more frustrated than friendly.

“No ganaron nada!” he yelled at the second group of protesters as we finally drove past. “You haven’t gained anything!”

Blockades are frustrating. The people who carry out the blockades understand that. Crushing poverty and deadly state repression are also frustrating. The fact that your colleagues had to lie in order to justify their frustration over being held up by the blockade would indicate that the inconvenience of being on the wrong end of a road block pales in comparison to the frustration experienced by the people carrying out the blockades. But most importantly – “You haven’t gained anything!” In fact, the movement that is erupting in Oaxaca has gained a lot. It has gained an unprecedented level of support from civil society. In the last two “megamarchas” that have taken place in Oaxaca, over 500,000 people participated. Over 30 communities in the state of Oaxaca have replaced corrupt local governments with popular assemblies.

Communities around the world have mobilized in support of the Oaxacan people’s movement (including in the US, where solidarity protests have taken place in New York, Chicago, San Francisco, Los Angeles, San Diego, and yes, even in Seattle.) The two national teacher unions in the United States (NEA and AFT) both passed resolutions in their national assemblies to send solidarity and financial support to the Oaxacan schoolteachers. And more than anything, the people of Oaxaca have gained their dignity.

—

source: reclaimthemedia.org