Gloria Muñoz Ramírez, La Jornada

Saturday, May 28, 2011

Translated by Scott Campbell

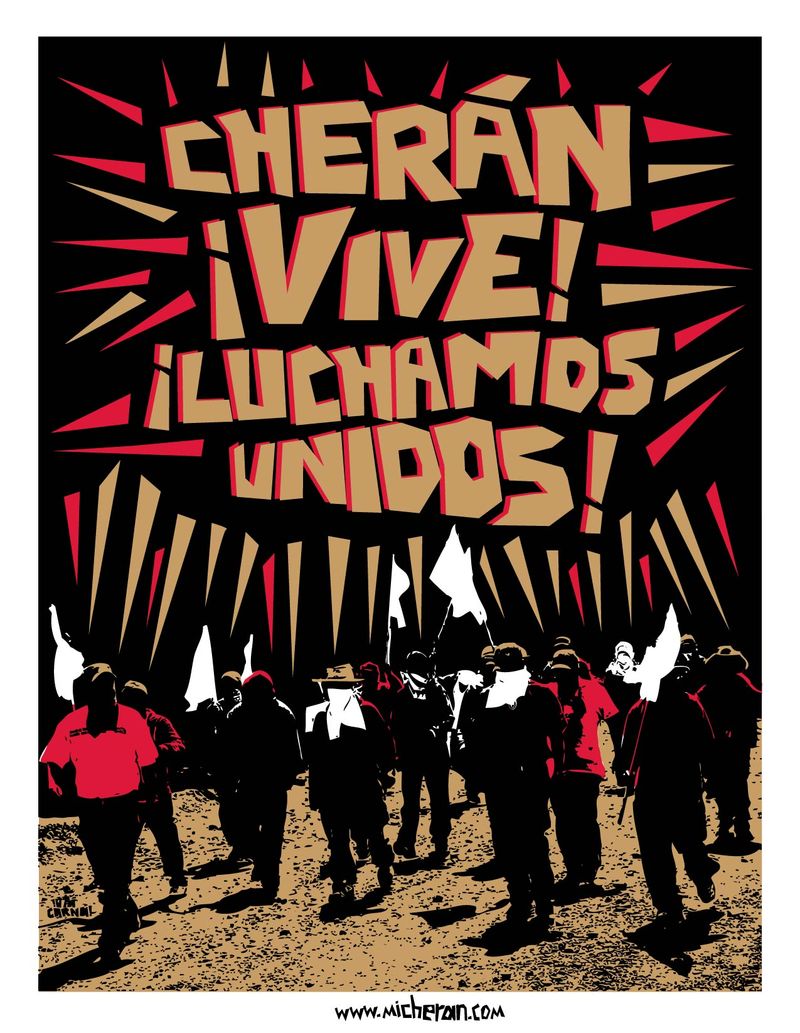

Cherán, Michoacán, May 27. In the face of government indifference and/or complicity, close to 20,000 community members have organized themselves for the past 42 days against illegal loggers who are supported by gangs linked to organized crime. Patrols, barricades of sandbags, trunks and stones at all the points of entry and 179 permanent bonfires in the four neighborhoods, have been in place since April 15.

Since then, the population has armed itself with sticks, rocks, machetes, pickaxes, shovels and anything they could, in order to confront those who “for the past three years have devastated the community’s forests, with the protection of armed groups and even the government, which has done nothing to stop them,” said one of the thousands of community members who guard the barricade which covers the path to Paracho.

Far removed from their everyday life, the women, men, children and elders of this town on the Purépecha plateau live in a permanent tension around the barricades, guarding the entryways so that no unknown person passes through. Dawn yesterday brought the news that armed men in tens of SUVs were getting ready in Paracho. It was a false alarm, but the patrols were reinforced, “just in case.”

At two in the morning, one of the guards assures that: “although we don’t sleep, we don’t lose strength. The government must attend to our demands: security and justice, an end to the devastation and punishment for those responsible so that we may live in peace.”

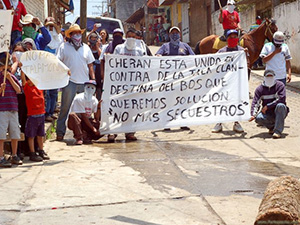

The government’s response hasn’t arrived, while the harassment and the threats have intensified. On May 22, “community member Miguel Ángel Gembe was kidnapped in Paracho.” Three days later he was able to escape “by a miracle” and returned to the community visibly beaten. It was confirmed then that which was suspected, that his kidnapping was due to his participation in the current mobilizations, as he shared that his captors interrogated him about the names of those who head the movement, warning him that “they’re all on the list.” As a result, the community members hold the state and federal governments responsible for whatever may happen to Miguel Ángel and the rest of the population.

It all began on April 15, when an event stretched their patience to the limit: “The illegal loggers entered La Cofradía spring, which supplies the entire community. A group of community members confronted them and kicked them out and since then we’ve been demanding justice,” says another of the indigenous from Cherán. Not one gives their name or shows their face, as a security measure against the permanent threats.

In this town, says another of the interviewees, “it comes together – all the injustices, the impunity, the complicity of organized crime with the governments, the indifference and evasion of the authorities, the ambition of the powerful…And also the organization of the people, who are angry, the defense of territory, the uniting of the women, the men, the children and the elders, all together to stop the logging of our hills, the kidnappings, the murders and the disappearances. Here, we are also fed up and we’ve gone into action alone to defend ourselves and to do what the government doesn’t want to do.”

A group of women from the neighboring community of Cheranastico approach one of the bonfires in the lower neighborhood (ketzikua). In Purépecha they communicate with the women on guard and prepare enormous pots of coffee, beans and potatoes with eggs. They talk amongst themselves and later one translates: “She says that they are suffering in their town also, that they are cutting down the forests, that they are very afraid. She says – the translator continues – that in their community they can’t go out to plant or let their animals out because they are stolen. She says that they are not free.”

The women, as in all popular struggles, take a leading role. They are strong and although they admit to being tired, they stand guard and make the food; they organize the cleaning, the supplies and the daily chores. With white hair, a blue scarf and weather-beaten hands, one of them replies to her anguished neighbors that they shouldn’t be afraid, that they should organize themselves as they’ve done in Cherán, that only then can they put an end to the injustice.

“Here you are united,” responds the elderly woman from Cheranastico, “but my town hasn’t had the courage because it’s small and they, the bad ones, are many and they’re armed.”

“Here,” says another woman at one of the bonfires in the Paricutín neighborhood, “what we want is peace and freedom. If we don’t defend our forests, there won’t even be one piece of firewood to leave for our children; there will be nothing left for them.”

Resistance against the clandestine logging, although scattered, began in 2008 when devastation in the Pacuacaracua hill increased. As of now, they report, more than 80 percent of the forest (more than 15,000 hectares) has been completed destroyed through acts accompanied by the “sowing of fear,” as the illegal loggers, from the towns of Capacuaro, Tanaco, Rancho Casimiro, San Lorenzo, Huecato, Rancho Morelos and Rancho Seco, savage the community with high caliber weapons.

Before rising up, they state, they knocked on all the institutional doors: “We went to PROFEPA, to SEMARNAT, to everywhere and no one paid us any mind. We also filed reports of the kidnappings, extortions and threats, and similarly they didn’t investigate anything. As a result they stretched our patience to the limit. We got fed up with keeping our heads down, as we saw nothing but hundreds of trucks filled with our trees and we didn’t say anything out of pure fear. But not anymore.”

Cherán has 27,000 hectares of communal territory, of which 20,000 are wooded; of these, 80 percent have been burned and logged (totally destroyed), and the other 20 percent has also been logged, but still hasn’t been burned.

A trip through the San Miguel hill allows one to see the devastated area. Hundreds of trunks lie in the paths. “It’s that the loggers only take the thick, lower parts, the rest they leave strewn around here,” explains one of the members of the traditional patrols, who is now in charge of security.

The roads into the forests are also under guard. Trunks and sandbags impede the path of the trucks, although, they say, “they still enter through other areas, because they’re not going to give up this business from which they get so much money.” How much? “Well, just do an accounting. Organized crime charges each truck 1,000 pesos for protection. Around 180 trucks left daily loaded with wood, which generated 180,000 pesos just for protection.

The big business, they explain, “is headed by a man known as El Güero. It’s a double business, as he sends workers to cut the trees and then they take them to his sawmills. But when other illegal loggers want to enter, he sells them protection so that they can remove the wood. As for us, well, we just watched, cowering, while all this happened.”

In these six weeks, the life of the community has completely changed: Now the municipal president doesn’t operate out of the government palace and the installations are practically in the hands of the community members. There are no classes in the elementary school or middle school, nor in the high school or in the Pedagogical University. A “dry law” is in place and they can’t ingest or sell alcoholic beverages; vehicular traffic ends at eight at night and 24 hour security is maintained throughout the municipal seat.

At the same time, the youth have taken charge of the cleaning and have organized a “good image” commission, which during these days is cleaning the streets with paint donated by businesses. They have also organized general cleaning brigades in which the whole populous participates, and in the streets, patios or under tarps the teachers in the community have organized classes.

In one of the improvised classrooms, Arly, a seven-year-old, says, “The bonfires are so that the bad guys who are taking our trees don’t get in. Without trees we are not going to have water and because of that there are bonfires, so that they don’t take away the forest.” And also, adds Karen, 11 years old, “we organized ourselves so that they don’t come to kill us. Now they are upset because they don’t come in; so they are angrier and because of that we have to be careful.”

As of now, in each neighborhood they have organized commissions for security, cleaning, good image, health, education, supplies, agricultural production and media. With all this, explains one community member, “through action, the traditional organization of the people is being exercised.”

Meanwhile, the government’s response doesn’t arrive. They’ve gone to the state and federal governments. At the Interior Ministry, they say, “they ask that first we demobilize, that we deactivate our organization. And they don’t give answers. We think that they don’t have the ability to confront truly organized crime. We have given them names and places where they can be found, but as of now they don’t do anything.”