x carolina

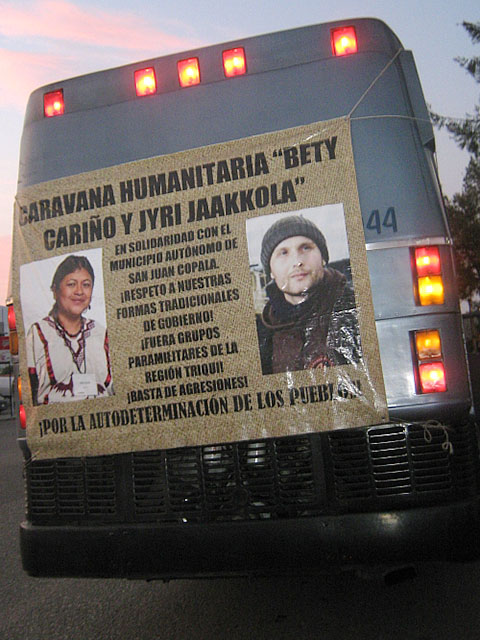

Six buses, several cars and vans, and a trailer truck packed with 35 tons of food, medical supplies, etc. left the Mexico City Zócalo for San Juan Copala, Oaxaca, at 9:20 the night of Monday, June 12. The name of the Caravana, “Beti Cariño and Jyri Jaakkola”, is in honor of a strong, much loved human rights defender who worked tirelessly for the unification of the Triqui people, and of a comrade from Finland who worked with the VOCAL organization on food sovereignty and climate change projects, also much loved and appreciated for his stance of solidarity. The two were murdered by the UBISORT paramilitary group led by Rufino Juárez on April 27 of this year for daring to participate in the first humanitarian caravan to the Autonomous Municipality. Their motive? Breaking through a paramilitary siege that has forced 700 families to live without light, water, school, medical attention and with very little food ever since last November 27.

Now the aim of the second caravan is the same, to break the siege. To get into the Autonomous Municipality to deliver the supplies, participate in an informational program on this dignified Triqui community’s experience with self-government, to record testimonies of human rights violations in a town where you can get shot any time you step outside your door. A town where dozens of people have been killed in recent months, including last May 20, when a commando of men described as “non-indigenous” shot down Tleriberta Castro Aguilar and her husband Timoteo Alejandro Ramírez, the natural leader and prime mover of autonomy in San Juan Copala.

But killings and acts of violence go on every day in the country. What made somewhere around 350 people decide to return to the scene of an ambush, knowing that something similar could happen again? For the people from San Juan Copala, it’s clear. Breaking the siege is a matter of life and death. And it’s also a top priority for keeping the autonomy project going.

For a lot of us, sick at our stomachs over so many outrageous abuses where the perpetrators go scot-free, the April 27 ambush was kind of like the attack on the Free Gaza fleet ––a moment when you say “things aren’t going to go on this way,” especially when some of the comrades hit hardest in the ambush immediately say “we have to go back into that territory with a much bigger human rights caravan”.

http://contralinea.info/archivo-revista/index.php/2010/05/09/sobrevivir-a-la-emboscada/

A brief survey of some of the caravaners elicits different responses about what led them to join in: “If I don’t go, what do I do with my rage? How can just shoot down people who went there in peace!” “They’re comrades. We have to stand by them”. “What kind of county do we live in were the police themselves have to ask Rufino Juarez’s permission to go into the area?” “I support what they’re doing in San Juan Copala. The least we can do is take them some food. ” “We have to defend autonomy to get rid of the parasites in the political class”. “So they can’t get away with what they did.” “To break the siege.”

But whatever each person’s reason for going may be, everyone is conscious of the risk. Some say they hope all the international support will pressure Ulises Ruiz to call off his dogs, but it’s clear that any one of us could die in San Juan Copala.

The previously announced press conference is not happening, at least not with the right people, the Caravan organizers. Most reporters show a decided preference for listening to speeches by Alejandro Encinas and other PRD congresspersons, who’ve shown their intense concern for the situation in San Juan Copala for a long time –at least two weeks. (See “Legislators and San Juan Copala Residents Demand Dismantelment of Paramilitary Group” http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2010/05/21/.) The racist position of promoting the PRD House Coordinator as the top leader will go on all during the Caravan.

Even so, many of the free and independent media projects fight to bring out what’s really happening. In an interview a couple of hours before the departure of the Caravan, spokesperson Marcos Albino Ortiz expresses his thanks for the support of student groups, social and professional organizations, and congresspersons. When asked about the excessive self-promotion of the legislators, which gives the impression that they’re the Caravan organizers, Marcos responds that they’re present “in solidarity and are not carrying their own banner”, and that the Caravan is organized “by the people who are experiencing the violence of the paramilitary siege in their own flesh and blood.” He stresses that the safe arrival of the Caravan is a top priority and says: “We’re closely watching its progress to see what the conditions are and to see whether it will be able to go in or not.” He sends big hugs to all the people who are planning solidarity actions on June 8 in Mexico City and different parts of the world against the injustices against Triqui people. He sends a message of thanks to the Other Campaign for its support for autonomy from the left: “We can’t let San Juan Copala’s autonomy be destroyed. We can’t bow down to State pressure and intimidation.”

Another bus is added to the original 5; as of yet, this one carries only a few people. As soon as we leave the city, the rules are read on each bus and everyone signs a statement promising to respect the decisions made by the Triqui Coordinating Committee, which knows the land and the people better than anyone else. We then organize ourselves into brigades of from 6 to 8 people to look out for each other.

Some of us sleep for a while before we get to Huajuapan de León at 6:30 in the morning, where we get a view of the crescent Moon in Aries in a sky streaked with shades of rose, blue, and yellow, that get brighter as the Sun comes up.

Comrades come in from the city of Oaxaca, Chiapas, Vera Cruz, Campeche, and Guerrero. And our spirits are lifted by greetings from comrades who’ll be protesting in Seattle, Portland, Boston, Vancouver, Barcelona, Paris, and several cities in Greece, Italy, and Germany, among other places.

While the brigades go out for breakfast, the Coordinating Commission meets for a long time to evaluate the constantly changing situation. Another press conference gets postponed. In view of a news flash about a provocative action being organized by PRI party candidate Eviel Pérez Magaña to “welcome” the Caravan to Juxtlahuaca, the route is modified in order to avoid this kind of confrontation. The protection of the lives of the people on the Caravan continues to be a top priority for the organizers. More news of danger comes in, leading to a reconsideration of whether or not conditions exist for the Caravan to proceed.

In the ongoing monitoring of the situation, reports are often fragmentary, contradictory, and confusing. Thisproblem get even more complicated when information and rumors are passed on by word of mouth. As is the case in almost any situation, there are differences of opinion over key issues. In spite of an overall distrust of the PRD due to its betrayal of all the indigenous people of Mexico in 2001, among many other things, some people insist that it would be impossible to advance safely without the party’s presence. Other questions come up. Is it true that Encinas has asked state and federal police to come in? How can we possibly expect them to protect us after what they did in Oaxaca and Atenco in 2006? Won’t they use it as a pretext to occupy the area?

At 10 o’clock, Commission members come out of their meeting. “Let’s go to San Juan Copala!” We grab our things and get on the bus in high spirits.

Now there are more than 400 of us, and we feel strong as we slowly move ahead in 22 vehicles. At 1:08 in the afternoon, a convoy of from 12 to 15 state police patrol trucks and other vehicles of the supposedly non-existent AFI and other police forces block the road going into Juxtlahuaca.

The representatives of the Autonomous Municipality demand a guarantee of safe passage for the Caravan to San Juan Copala from the Oaxaca State Attorney General María de la Luz Candelaria Chiñas. But she’s not interested in talking to them. She’d rather talk to the congresspersons. She assures them that several different agencies are working on security issues. She tells them that the Caravan will only be allowed to go on if the leaders hand over the documents of all participants, a condition that is rejected as a violation of the right of freedom of movement.

At 1:25, most of us get off the buses and start calmly walking ahead, circumventing the police convoy. We’re all happy about making it clear they haven’t been able to intimidate us. A couple of people suggest that we could just keep on walking to Copala, carrying the supplies in with us. When the police cars have to move on ahead of us, we get back on the buses and go on to the town of Santa Rosa in the Mixteca Region. From this time on, most of us don’t get much information about the negotiations due to security considerations. A lot of the following details only came out in subsequent conversations or reports.

At Santa Rosa there are more talks with the Attorney General. To make it short, she assures Alejandro Encinas that freedom of movement exists in Oaxaca, but the government can’t guarantee it.

She says that Oaxaca state police agents and those of the AFI (that doesn’t exist), SSP, PFP, PGR, public prosecutors, human rights officials, and state legislators are all here to provide safety for the Caravan, but that there is no way to give “a 100% guarantee that there will be no problems.” And why is this? Ahhh, of course. It’s because the government simply “has no control” over these “violent Triquis” or over “historic problems” between the MULTI, UBISORT and MULT organizations. She washes her hands of the matter: “The government is not responsible for any act of provocation between them.”

Candelaria Chiñas has several suggestions, including one that UBISORT should stand guard over the Caravan, another that UBISORT should participate in the negotiations in Juxtlahuaca, and still another that the Caravan should hand over part of the food and medical supplies to UBISORT ––conditions that are obviously an insult to the Autonomous Municipality. And where do these original ideas come from? Well, if truth be told, they’re demands made by Rufino Juárez, who doesn’t even blush about dictating the terms of the “dialogue”.

Doctor Adrian Ramirez, President of the Mexican Human Rights League, LIMEDDH, asks how it’s possible that you officials have dealings with “somebody accused of serious crimes that you can’t even control!”

Once again, Marcos Albino and Omar Esparza demand that the authorities investigate the murders in the first caravan and that they guarantee the entry of the Caravan.

Another of Rufino Juárez’s messengers, the President of the State Human Rights Commission, Heriberto Antonio García, states that there are Triquis who oppose the entry of the Caravan. “Rufino Juarez is there a little further on with a group of people….and we think there could be some kind of conflict.” He assures everyone that “they want dialogue. We’ve urged them to allow passage of the Caravan without any obstructions… but they’ve been totally clear about the fact that it is not convenient for the Caravan to enter right now.”

In other words, UBISORT’s word is law. Has the State created a monster it can’t control? Or is it just that it’s not to its advantage to control it right now?

As the Caravan gets into the Triqui Region, the nature of the police operation changes. Now hundreds of state and federal police not only ride around in pickups. They take up positions at every 50 to 100 yards on the ridges, slopes, and other strategic points with their assault rifles pointed at the Caravan. Are they the police? Military troops? Militarized police? Policified troops? Paramilitaries? Parapolice? How can we tell? They all look alike and act the same way.

“They aren’t there for UBISORT”, says one comrade. “They’re there for us.”

From this point on, no one is allowed to get off the bus under any circumstances. Several of us try to document the operation from inside.

There are more talks in Agua Fría, a new evaluation, and another decision to proceed with caution. When we get to a rise called Diamante approaching La Sabana, the police offer to take a congressmen and, apparently, a human rights defender to verify whether or not UBISORT has blocked the road. They find that a row of UBISORT paramilitaries are backing up a row of women and children from their organization at the entrance to San Juan Copala ––an astute tactic to make it seem in the press that the Caravan is against indigenous women and children.

Around 5 o’clock in the afternoon, it’s reported on the buses that “there were gunshots,” that “security conditions do not exist for the Caravan to advance,” and that “we will return to Huajuapan.” Mission aborted. Many of us strongly disagree with the decision and think that by turning back now, we’re losing our best chance to go into Copala and break the siege. We think the mood of people willing to go in despite the risk is a key factor. The Commission considers what we say, but sticks to their decision. They don’t want to risk the life of a single person.

That night, there’s an event at the Flamingos meeting hall, where Jorge Albino and Omar Esparza call for intensifying national and international pressure to break the siege around San Juan Copala. Given the complicity of the State with the paramilitaries, they plan to rely on international bodies like the Red Cross to deliver the supplies. If this doesn’t work, there’s a proposal for a women’s caravan to try once more to break the siege.

After the event, there’s a march and rally in the streets of Huajuapan, and the next day, more talks and evaluations in the city. There’s also a march the next day in the city of Oaxaca, with a contingent supporting San Juan Copala. On Thurday, June 9, the Caravan is welcomed in the Mexico City Zócalo with hugs, smiles, a tear or two, and a lot of reflection about how to move ahead on the road to autonomy ––the road to San Juan Copala.