By Maya Zazhil Fernández

As Chicago makes international headlines with its images and stories of extreme turmoil, it is imperative that we examine the history and context that led to the events which transpired from May 30–June 1, 2020 in the historically Mexican neighborhoods of Pilsen, Little Village, Back of the Yards, and in Cicero, IL. While it may be painful to acknowledge that members of our community took part in the violence we’ve been experiencing the past few days, we must always remember that the central culprit has and will always be white supremacy and all of the systems that support, protect, and perpetuate it. We must also all step up to the task of unpacking what happened, who was impacted, who benefited and why it was able to occur in the manner it did.

Chicago, by design, is one of the most segregated cities in the world. The South Side consists of large tracts of Black neighborhoods interwoven with tracts of Mexican neighborhoods. The North Side is home to a diverse immigrant community, as well as historically Puerto Rican neighborhoods and a large white presence. To the east, Lake Michigan, and to the west, a continuous horizon for expansion and ongoing displacement of the already established communities in the city. Throughout the city, neighborhoods are separated by bridges, viaducts, or boulevards, where a Black person can live 3 blocks away from a Brown person and never cross paths. There are many political, economic, psychological, and cultural repercussions of living in a blatantly segregated city. Living with constant geographic and visual reminders of how drastically different the quality of life is because of your racial and cultural identity is an agonizing experience fueling confusion, hate, and violence.

Following the genocide of the original native peoples, including the Potowatami, Chicago was settled by European colonizers in the mid 1800s, and quickly grew to attain its status as the largest city in the Midwest, receiving the white European immigrant populations of the late 1800s – largely, Irish, Italian, Polish, Czechs, and Germans. In the early 1900s, through the Great Migration and the World War I era, Chicago was a destination for the African American Great Migration from the South, and Mexican immigrant laborers in extremely large numbers and in a very short time. At the time, white Chicago, instantly felt its comfort and power threatened by the sudden arrival of people of color, and quickly organized itself and the city, forcing the incoming arrival of people of color to settle in strategically designated areas of Chicago that would ensure keeping them hidden, separate, and invisible to the urban identity of what they hoped would grow to be the largest, and most important city of the United States. Furthermore, these neighborhoods were ethnically segmented, as the Italian, Irish, Polish, Greek, Czech, Mexican, Puerto Rican, Indian, Chinese, all established their own neighborhoods, or multiple neighborhoods throughout the city, which have remained until the present day. Though this thorough fragmentation permitted the survival of cultural practices and identities, it also greatly contributed to ongoing racial and ethnic tensions, fueling historical local rivalries between Mexicans and Italians, Mexicans and Puerto Ricans, Polish and Lithuanians, Koreans and Chinese, and the list goes on.

Following the U.S. Housing Act of 1937, Chicago began building its many public housing projects, creating another framework through which the city could continue to legally implement racial segregation. This framework imposed geographical boundaries for communities based on race and limited distribution of wealth and resources, and promoted a proliferation of drugs and weapons. In the 80s, the U.S. government facilitated the trafficking of crack-cocaine to urban communities nationwide, targeting public housing projects and Black neighborhoods, which led to what is commonly referred to as the “crack epidemic.” Though the Latino communities lived in separate neighborhoods, they suffered a parallel experience of addiction with PCP [embalming fluid]. Black and brown communities were intentionally flooded with highly addictive drugs by organized crime with the complicity of the U.S. government while simultaneously being denied access to resources for economic development, mental health services, healthcare, and substance abuse treatment resulting in cycles of violence, addiction, and trauma, reproduced across generations.

The orchestrated establishment of these segregated neighborhoods, was one of the most important building blocks of a local, systematic political structure through which the city could easily distribute, or withhold distribution of resources, and through which it could contain its power and wealth. Whatever scraps of resources were funneled into the segregated neighborhoods of color naturally became a point of contention in the battle between the Black and Brown communities of Chicago. The other building block of this structure was the creation of the CPD (Chicago Police Department) – at its inception, an all- white-men, armed organization whose job was to “serve” white Chicago and “protect” its privilege, wealth, and power from the “threat” of Black and Brown people. Gangs of color, such as the Latino gangs in the Latino community and the Black gangs in the Black community, began to emerge, primarily as organizations defending their communities from the violence and brutality of the racist police and of white gangs, and as organizations attempting to obtain their own means of wealth within communities that had been structurally deprived from access to resources. Despite these intentions, the repercussions of communities of color being plagued with increasing poverty, addiction, and violence corrupted these organizations, causing them to harm, more than serve or defend their communities.

The Chicago experience is one filled with beautiful testimonies and expressions of cultural resistance, resilience, and ingenuity, but the consequence of its structural racist and xenophobic history is a ghost that haunts the lives of Chicago’s Black and Brown children, obstructing their path to healing, solidarity, and revolution.

Following the murder of George Floyd at the knee of police officer Derek Chauvin in Minneapolis on May 25, 2020, people took to the streets on May 26 to protest the lack of any arrest or charges against the officers involved with the murder. On May 27, the protests in Minneapolis escalated with rioting, looting, and the subsequent police repression, while many other cities in the country began to protest in solidarity. On Friday, May 29, the same day that Derek Chauvin had been arrested and charged with third-degree murder, Chicago joined the rest of the nation in protest, expressing its rage at the lesser charge given to Derek Chauvin and demanding that the other 3 officers involved be held accountable as well. The other 3 officers were not charged/arrested until June 3.

On Saturday, May 30, the demonstrations downtown continued, quickly escalating into riots as a response to both instigation as well as blatant police antagonism. Businesses throughout downtown were broken into, looted, set on fire, cop cars were set on fire, people were shot, and protesters were beaten, brutalized, and arrested by the CPD. In an attempt to “control” the situation, Mayor Lightfoot ordered the lifting of all the steel bridges that cross over the Chicago River, providing main entries to downtown. Subsequently, all public transportation to and from downtown was suspended, essentially trapping protesters in a contained area. After physically eliminating all possibilities of evacuation for thousands of people downtown, at 8:30 pm, the city announced a 9:00pm curfew, instantly turning protesters into lawbreakers and justifying their arrest. Both arrests and escapes to safety continued until early the next morning, but the affairs of that night initiated a wave of rage, violence, and retaliation across nearly every sector of the city that we have yet to see the end of.

On Sunday, May 31, the city reinforced the blocking off of all access to downtown with blockades and checkpoints, and continued to indefinitely suspend public transportation, forcing people to redirect their rage towards other accessible areas – their own neighborhoods. Beginning that morning, the city ignited, figuratively and literally. Businesses, buildings, and vehicles all over the Black and Brown South and West Sides of Chicago were continuously broken into, looted, and set on fire at all hours of the day. Suspending the public transportation system and closing off highway exits not only kept people away from downtown, but also encouraged them to utilize vehicles as their transportation, creating a fast speed highway of chaos on most city streets, intensifying the overall state of unrest and anxiety felt throughout the neighborhoods. While the self-destruction transpired in these historically over-policed neighborhoods, the presence of police at this time was almost entirely absent. Though the city was reporting shortages and maxed out capacity of its law enforcement, it became clear that police had been intentionally and disproportionately assigned to different areas of the city based on the racial makeup of said communities. CPD also deliberately chose not to act in response to the ongoing activity viewed in multiple social media live videos in which police were observed standing around, permitting looting. In a most blatant example, more than 10 police officers were recorded napping, snacking, and waiting out over several hours inside Congressman Bobby Rush’s office that had been broken into, while looting and shootings were taking place just down the street. These events were occurring simultaneously as protesters continued taking to the streets and continued being attacked by police.

The news and media began pushing the completely false narrative that the protestors were looters and were primarily Black, which was only amplified by pre-existing, internalized racism and historical trauma. This caused a natural human reaction to defend one’s self, home, and community, but thanks to the structural setup, and with a little help from the CPD, the local government, and the national fascist agenda, it quickly became a paramilitary operation externalized as a race war.

Once local businesses in the communities of color began to get hit by looting, several Mexican gangs, began patrolling the streets, in the name of “defending their communities’ businesses from looters,” who as mentioned previously, the media and the city made out to be exclusively Black. Instantly, this became an assignment to essentially hunt and harm all Black people in sight. Videos and reports immediately surfaced and circulated on social media of Latinos, mostly Mexicans, throwing bricks at any car with Black passengers and beating or shooting any Black person who entered the area, including actual residents. In Little Village, a Black woman was shot for crossing the street. In Cicero, a Black man in a car was attacked with a pole. The news reported a total of 85 people shot and 25 killed, though we know the number is much higher due to the negligence and lack of response on behalf of the city.

Though the ingrained racism that exists within Latino culture and identity permitted these attacks to occur, multiple pieces of evidence also surfaced, clearly uncovering the CPD as collaborators, instigators, and architects of a race war between the Black and Brown communities of Chicago. Videos of Mexican gangs “assisting” the Chicago police in “capturing” the “Black looters”, videos of the Chicago police informing Mexican gang members of what cars the “looters” would be coming in and where they were located, and audios of police officers intentionally permitting the rival Black and Brown gangs to shoot at each other were all amongst the captured media. In the following day, the implicit impunity granted to Mexican gang members by the CPD, to be able to engage publicly and openly in illicit activities for which they were previously apprehended and penalized, suggests a larger understanding and/or agreement between the Mexican gangs and the CPD to implement and enforce violence against the Black community on the CPD’s behalf, though it is unclear as of now what level of formality this agreement may have. In other words, the white supremacist state ultimately were able to psychologically, and possibly formally, contract a Mexican mercenary force in Chicago as a paramilitary group to continue and carry out their racist agenda of black genocide, all the while eliminating any traces, fault, or responsibility of their own.

Monday, June 1, was confirmation that what had begun to unfold over the weekend, was going to be a long, bloody, painful war with many casualties. Gangs from the Black communities that border Latino communities on the South and West Sides of Chicago began their retaliation in response to the unjustifiable acts of violence made against their community by the Latino gangs, and both sides continued to battle each other with racial slurs, physical attacks, and automatic weapons. One of the significant events that unfolded on this day happened in Cicero, IL.

Cicero is a suburb located directly west of the Mexican Little Village and the black Lawndale neighborhoods of Chicago, and directly south of the black Homan Square neighborhood of Chicago. Cicero was settled by European colonizing immigrants seeking to leave the density of near southwest Chicago, Pilsen and Little Village neighborhoods. As those neighborhoods became increasingly Mexican, many more whites fled to Cicero in an attempt to escape living with or near the new brown immigrants. Cicero had also established its identity with a strong Italian base, home to Al Capone and the Italian Mafia. Functioning autonomously from the city of Chicago, Cicero created its own political infrastructure that upheld and protected white supremacy through a culture of corruption and proximity to the Italian Mafia that remains in play today.

In the early 2000s, Mexican immigrants were no longer able to afford the ongoing gentrification in the communities of Pilsen and Little Village and began settling in Cicero, transforming its population from 5% to 85% Mexican in less than 10 years, as white European descendant residents kept relocating west, once again fleeing brown immigrants. Today Cicero is a primarily Mexican town, though the government and local authorities remain predominantly white and retain notoriety as a corrupt, racist entity.

What happened in Cicero on June 1 was an extension of what the Latino gangs had been doing in Chicago, supported by Cicero’s historically racist systems. Mexican Cicero residents and business owners continued to target and attack Black individuals passing by in their cars, walking, or on the bus. A photograph emerged from that day showing business owners and residents sitting on the roof of a dollar store with automatic weapons, ready to shoot at any “black looters,” all while local Cicero government and law enforcement permitted it. Four people were shot, two were killed, and over 60 were arrested that evening in Cicero.

Starting Tuesday, June 2, there were reports of truces being made between the Black and Brown gangs as many Latino youth in communities on the south and west sides such as Pilsen, Little Village, Back of the Yards, Gage Park, and including Cicero began responding to the crisis, organizing themselves to show up and defend Black lives by taking the streets, challenging the Latino, anti-Black narrative and marching for Black and Brown unity. Black and Brown solidarity marches occurred daily during the weeks of June 2–June 14, many, youth led. This seemed to have helped calm the waters a little, while there were more reports of the older gang members having trouble implementing the truce with younger members, sectors of the gangs choosing to not honor truces. The shooting/attacks continued, though in lesser numbers, and always with the risk of resurgence.

In these times of cyber-warfare, what is also suspected is a contrived use of social media to promote, popularize, and normalize the idea of a race war in Chicago. Various social media accounts posting about the “race war” were tracked to the same IP address, resulting in an almost instantaneous collective awareness about a race war, when hours before, nobody outside the affected neighborhoods had any knowledge of it. It also raised suspicions of the origins of both “flyers” that began to circulate “scheduling the shoot out” of Mexicans vs. Blacks and text messages with internal information of gangs “breaking truces” and “calling for retaliation” between races and ethnicities which were never proven to be true. Though it is extremely difficult to prove who was behind the creation and circulation of said messages, all evidence keeps supporting the case for orchestration of this race war we are currently living by the powers that be, meant to maintain the white supremacist structure through the constant attack and attempted genocide of our Black and Brown communities.

Artwork by Sara Briseño Torres

Artwork by Sara Briseño Torres

The facts are that between May 30, 2020–June 3, 2020, Chicago had not seen a single hour without protests, shootings, lootings, or fires; the soundtrack to the city consisted of 24/7 sirens, helicopters and gunshots; the number of lives lost has yet to be quantified nor will it ever be; and the amount of pain and trauma is equally unquantifiable, and likely irreparable. It is important to note that throughout all of this, Chicago has also experienced the same attacks and violence as the majority of cities in this national uprising: attacks and threats from armed white supremacist groups; abuse and brutality from local law enforcement; infiltration of movements in the form of planting weapons, inciting riots, and antagonism. But what we have been experiencing in the South and West Sides of Chicago has been what feels like a parallel universe, invisible to the rest of the city or to the national and international scope of news, though it stems from the same cause and perpetrators.

As we continue to fight for our survival, let us outline and recall the 4 most important factors that have led us to this point in Chicago’s history:

1. A capitalist system where our human rights are monetized, and our access to basic resources needed for survival is racialized.?

2. A geographic, segregated landscape designed to enforce and protect white supremacy.?

3. Colonization and generations of internalized historical trauma resulting in the weakening and erasure of cultural identity.?

4. The increasingly facilitated access to weapons in communities of color.?

As of now there is no way to know how or when we will be able to surpass these dark days of violence, but what we do know is that even then, the fight is far from over. Even if resolutions are made and demands are met, the damage to communities of color has been done, and will never be forgotten. We are tasked with the challenging work of facing the generations of racism that are ingrained in our cultures as a result of centuries of colonization, as well as the task of dismantling the systems and structures in place that were built on and have thrived on the enslavement and oppression of people of color. The path that awaits us is a long and hard one which can only be successful if and when we commit to the painful, but victorious process of forgiveness, healing, re-imagination and transformation.

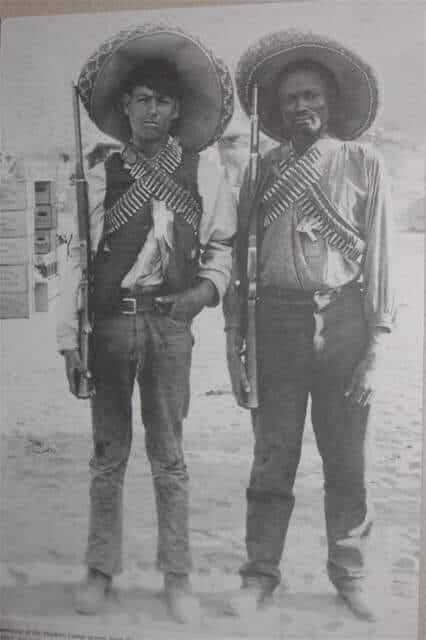

Photo by Photo by Mateo Zapata

Photo by Photo by Mateo Zapata